It’s probably no secret by now that most of the work done by the Hiroyuki Imaishi-You Yoshinari team contains some sort of political commentary ; however, when looking quickly at works like Kill la Kill or Promare, one might be led to believe that this commentary rests on a simple-minded manicheism : bad fascists/capitalists are bad, so to speak. Such an analysis might also apply to the team’s last, Brand New Animal. But here, leaving a more detailed look at the former works for later, I’ll show that BNA in fact deploys a complete and in-depth political meaning. “Complete and “in-depth”, that is both intensive and extensive : it’s in-depth, because it prolongs Trigger’s repeated artistic statements on identity and personal freedom ; but it’s also complete because it does not stop on a utopic answer to the problem it raises. In fact, BNA extends its gaze to a systematic and realistic portrayal of oppression and its structures ; and it’s here that its greatness lies.

The one and the many : the question of identity

The fact that BNA is about discrimination, minorities and identity, should escape no one and seems pretty obvious : the setting makes that clear, as the beastmen’s position is always a fragile one, on the verge of being overtaken by hostile humans. It is them who, after all, carry either financial and technological power (in the case of the Sylvasta conglomerate) or political and military might (in the case of the Japanese government).

Such a situation would speak to most oppressed communities, but just as in Promare, it seems that BNA targets one in particular. Indeed, the color scheme that both share is not just a nod to vaporwave esthetics : it is without a doubt inspired by the colors of the Transgender Pride Flag. While it’s most obvious in the case of Promare, which uses lighter colors closer to that of the flag, this lighter color scheme can also be found in Michiru’s eyes, and considering both works share the same general thematic, I believe it likely that transgender and, more widely, queer communities are at the heart of BNA’s message.

The show’s world is one where identity is predefined : it makes clear that the difference between beastmen and humans is not just surface-level, but is a genetical one. There is no doubt, therefore, that one cannot switch from one to the other – unless in the cases of Michiry and Nazuna, that is. What’s most interesting with them is that their identity is multiple, and this in many aspects. First, it’s not biologically determined, but has been engineered by humans : in other words, it isn’t a natural, unchangeable essence, but something in-between that may be modified. That means that as humans, they’re also beasts ; and as beasts, they’re also humans. They’re not just one thing, but both at the same time.

But there’s more : because even as beasts, their identity is more complex than that of most beastmen. Indeed, the “species” to which the girls belong isn’t one that you can just find in the natural world (a wolf, a mink, etc.), but they’re species with a strong mythical aura, and whose most distinguishing feature is shape-shifting : Nazuna is a fox, and Michiru a tanuki. By definition, they exceed categories and classifications, as Michiru’s many successive forms show. And obviously, this shape-shifting ability is show in a positive light, and is what enables the good guys to win in the end.

Considering this, Michiru’s character arc mustn’t be understood in terms of “she accepts that she’s become a beast”. In fact, what Michiru realizes in the course of the show is that she’s not a beast – but not a human either : any category of identity imposed on her is just wrong. Her conversations with Shirou that come up from time to time help the viewer understand the evolution : whether she wants to go back “home”, as a human, or stay in Animacity. However, I believe that, with what I just said, her declaring that she’ll stay in Animacity doesn’t mean she relinquishes her humanity. The reason she stays is because she “likes it here” and because it’s here that there are “things that only her can do”, but that’s not a rejection of the human world. In other words, one could say that Michiru doesn’t choose – but that’s all right, because she doesn’t have to.

The main crux of conflict in the show lies in this question of a predetermined and univocal choice : the apparent way of the world is that one has to be one thing and one thing only, whether they’ve chosen it or not. Paradoxically, the Sylvasta family embodies this to the utmost, but also to the most contradictory : with their obsession on purity, they obviously represent the darkest, most ideological form of oppression, whether racist or heteronormative. But at the same time, Alan’s nature as a beastman is indistinguishable from that of a human ; and unlike in the case of Promare’s Kray Foresight, he doesn’t seem to explicitly represent internal repression of his other identity. But that duality of identities is exactly the opposite of Michiru’s : whereas she is neither human nor beast, Alan is both, and perfectly, human and beast. As a human, he is handsome and successful ; as a beastman, he is one of the most powerful beings of the species. But what BNA seeks is not perfection, because perfection is still unilateral : to be the perfect beastman is still to be just a beastman, to reduce one’s identity to only that to the point of becoming an archetype – and as an archetype, perfection can also become the caricature.

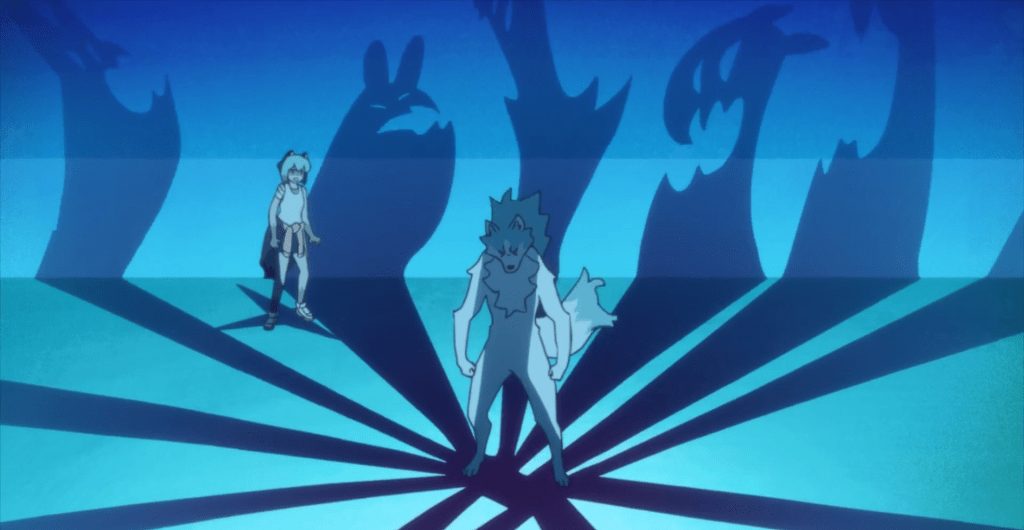

In this aspect, Alan stands in contrast not only with Michiru, but with Shirou who, as the god of the beastmen, can be thought to represent a kind of perfection. But here, his power does not come from the unicity of a dictatorial perspective : it lies in the acknowledgement of his plural identity. In his final fight with Alan, Shirou invokes the souls of all the dead beastmen that live within him ; and the shot, in which he projects not one, but multiple shadows, makes clear that even though his personality is one, his identity stands for many.

In other words, BNA clearly makes a stand against any normative assignation of identity, whether it is one based on gender, race, or any other criteria. But while the main character can change shape at will, I don’t believe it just says that we can become whatever we want if we just want it hard enough – that would be naive. The points I just made about the opposition between unity and plurality show that to make one’s identity a liberating affirmation and not a cage used to pin one down, hard work is necessary. What’s needed is first a general dismantling of the opposing discourse, held both by humans and beasts and presented like an obvious truth of science. Then, after being acknowledged as a possibility, Michiru and Nazuna’s arcs show that plural identity needs to be actively embraced – even though that is not an easy thing to do. While it does primarily include it, such a process goes beyond queer identity and communities : it is a way to resist all forms of power, whether political or economical.

Images of oppression

The points I just made could, I believe, be made in a similar manner for most of Hiroyuki Imaishi’s works : in that sense, BNA is but the last in a series of politically charged series with a common and consistent message that defines personal identity as 1) a personal and political concept, 2) something that is historically constructed and can be changed, and 3) the main stake of all endeavors, again political and/or personal of liberation and emancipation. However, BNA does not limit itself to such ideas, which have become staple Trigger and somewhat of a compulsory trope. What makes it stand out is that it complements these theses with a systematic and, one might say, realistic, image of oppression in its diversity and complexity. This relies not so much on character development and conflict, but rather on world-building. I would say that BNA’s world drives home three things, that I will study one by one.

1. Class structure doesn’t mean binary opposition. The setting of the show reifies class structure, almost to the point of caricature or allegory. Indeed, one might think at first sight that in BNA, there are no classes, but only species : humans, and beasts. As I have said, the difference is a genetical one, and even though the plot and themes end up dismantling it, the show initially rests on a binary, almost manicheistic opposition between oppressors (humans) and oppressed (beasts).

But saying that would actually be paying no attention to BNA : because even if it true that humans are portrayed in an entirely negative light (despite Michiru’s claims that “they aren’t all bad”), beastmen society is far from being just a victimized community that does its best to survive and resist discrimination. First, to stretch things a bit, it could be argued that it is ideologically diverse : while they are apparently a minority, there exist radical anti-human beastmen as well as beastmen mercenaries and hitmen working for humans.

More importantly, Animacity is in itself an entire society, with its own inequalities and class structure ; in other words, while all beasts receive discrimination equally from humans, there exists intra-beastmen discriminations and social conflicts. This is especially pointed out in episodes 2 and 5.

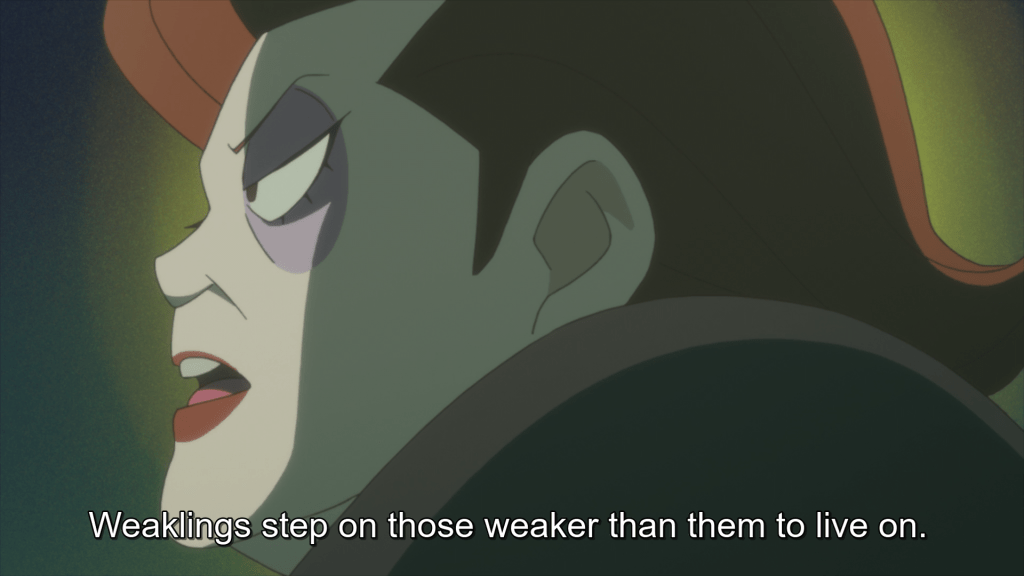

In episode 2, Michiru discovers, and becomes involved with the underworld. More than just a plot contrivance, its existence is in itself something telling : first, that Animacity and beastmen society is developed enough to have grown an underworld, and second, that beastmen in general have an association with clandestinity and criminality – that is, they are not natural allies of state authority even though they set up their own in the city. It also reveals that Animacity is not the ideal place Michiru thought it would be – a paradise for beastmen. In fact, it is the kind of place where struggle for life reigns ; but it is a twisted interpretation of it, corrupted by the fact that beastmen already live in misery : it is not the strong who triumph over the weak, but those already weak who have to step on those even weaker than them. This implies that the strong would not need to resort to such behaviour. In other words, oppression fuels more oppression as the oppressed resort to violence and criminality to survive in an already difficult situation.

This very situation already takes away a large part of the manicheism one could accuse the show of. But it goes even further, as this episode focuses on a particular space : the body. Considering the importance of appearance and shape-shifting in the show, it is already clear that the body is not a neutral object : it embodies one’s identity, as the relative regularity of its shape (or lack thereof, in case of Michiru) allows one to be recognized as a single individual. In such a context, episode 2 is vital, because it shows that the body, and therefore the identity it marks, is the first target of some systems of oppression – here, capitalism and market structure. Indeed, the episode confronts us to the fact that the body itself becomes a commodity for those who do not have anything else to sell to make a living – that is, women who become prostitutes, and children who are sold off. And while in the end, the children are taken care of by the public authorities, this solution and Michiru’s call to solidarity both ring hollow : it is clear that these are not enough, because what makes such situations possible is a more structural and wider problem.

Episode 5, however, contrasts against this message. It shares its analysis : there are slums in Animacity, showing that everything is not rose-colored ; and the running gags of the lifetime payment plan and different kinds of frauds the bears are victim to show that the exploited are also exploited by their fellow beastmen who live off their poverty. However, they also represent a more welcoming side of Animacity : when Michiru says that she’s a tanuki and can’t play in the Bears team, they answer that they “don’t discriminate against types of bears” : this is the first time in the series that Michiru’s identity is not assumed by an external person. This may be meager consolation in the face of apparent economical distress, but it’s as if those in the lower levels of society are too low to even care about identity – and are therefore the most open.

2. Oppression isn’t just discrimination and violence. While what I’ve just said shows that BNA is lucid about systematic forms of oppression, it’s still a rather simple portrayal, as discrimination is still shown to take the form of physical violence or poverty. But if oppression is something systematic, it is far more extended and vicious than just that ; and BNA also takes it into account, in its fourth episode.

In another attempt to enrich its image of Animacity, the episode first shows that the opposition between beasts and humans is not completely radical : Nina’s popularity on social media and fascination for the human lifestyle demonstrates that both races more or less live in the same way and that humans exert a strong, positive attraction. It is apparently reciprocal, as when Nina and Michiru take part in a human party, they realize that its theme is beastmen, and all the members admire Nina’s beast form.

Before things go south in the end of the episode, we must note some things about this situation : this party is apparently held by very privileged people. It takes place at the top of a skyscraper, in a place big enough to hold hundreds of people, have an aquarium and a pool. And that’s just a birthday party. Moreover, Nina herself, even if she’s been invited as a social media acquaintance, is probably among Animacity’s richest as the daughter of the criminal syndicate’s leader. What this setting means is that the interest exhibited for beastmen is something enjoyed by the well-off in human society, and that it is reciprocal. And as the end of the episode illustrates, this interest is very surface-level : these wealthy humans only seem to care for beasts as an esthetic, and would probably never consider alleviating the material distress beastmen live in.

Then comes the main crux of the episode : the revelation that this esthetic engagement with beastmen is in fact as harmful as actual, material oppression, and is just the same kind of discrimination. First, because it’s hypocritical : these humans appreciate the spectacle of beastmen, but in the end, they still consider them as a sort of different, inferior, maybe dangerous beings. If they tolerate their company, it is only in submission : were Nina to refuse to show herself off and express an actual individual desire, she would no doubt be met with more hostility. But even if there may be cases without hypocrisy, as it might be with the girl who holds the party, the situation remains harmful, because it involves no actual understanding or dialogue. Indeed, Nina ends up locked up in an aquarium, another symbol of entrapping esthetical engagement, not out of direct hostility, but out of care : she looked tired, and is a fish, so she would naturally be at ease in an aquarium. But this only threatens her life, because while Nina is at ease in water, it’s not her living environment – and the humans ignore that because they act on their own presuppositions, even if it is with goodwill.

This is another illustration of the fact that the problems are structural, and not just surface-level things that can be met with solutions like the hero shouting very loudly and defeating the bad guys. What’s involved here is an entire set of immediate opinions and assumptions – one might say an entire culture – that gives itself a good appearance but in fact encourages more discrimination and harm.

3. Diversity isn’t that easy. Finally, BNA hammers down the idea that there are no easy solutions by the fact that its plot itself revolves around a possible solution to the problems it points out. Indeed, against forcibly assigned identities and a hostile cultural environment, it might be easy to answer, along with Michiru, that we just have to take matters into our own hands and live together in a world based on solidarity, understanding and diversity. But things are more complex than that, and this position is as much an ideal as it is wishful thinking.

First, I think I’ve made clear that Animacity is not this kind of utopia ; it is not because it still has a harmful class structure and a large part of its population lives in poverty. But it’s also not, because it is in itself a contradictory space : at the same time a safe space and a ghetto. It’s obviously a safe space because humans are not to be feared there, and beasts can live as beasts without having to be afraid. At the same time, however, it’s a ghetto : outside of Animacity, beastmen are in constant danger, and without the help of those same humans who want to get rid of them, the city would never have been established ; and in the end, we see that having all of them in a single place makes their elimination more easy and efficient.

But more importantly, coexistence with different kinds of people isn’t something obvious either, even among beastmen : the very nature of the Nirvasyl syndrome is that it’s triggered by too many different species living together in a shared space. This is described as a resurgence of beastmen’s animal instincts : in other words, this is not some surface-level problem that can easily be brushed off. The show resolves it quickly, as Michiru’s blood acts as a serum that cures the syndrome. But the main question remains : communautarism and discrimination may very well be a natural reaction. That is why, even though the syndrome has been cured, the show ends with a lot of things that remain to be done : the social, economical and cultural conditions that make coexistence between beastmen, and with humans, have not been fundamentally solved. BNA acknowledges that such an endeavor would be long and difficult, and this humility contributes to make its portrayal stronger and more relatable ; but it also invites us to get to it now, because it’s lengthy and grueling work, and every new hand is a welcome one.

Beautiful analysis. Thank you for sharing.

BNA covers a more inspiring message of what I was initially aware.

LikeLike