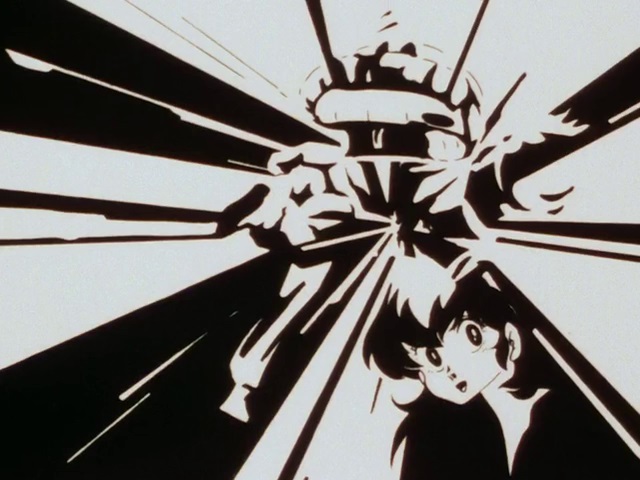

Cover illustration: a key frame by Kôji Nanke from the first opening of Urusei Yatsura

This article is part of the History of the Kanada School series.

How did Yoshinori Kanada go from being “merely” a very talented animator to one of the most influential members of the anime industry? That’s a fascinating question, and yet one I haven’t seen much precise discussion of. The world of anime was much smaller then, but it was nevertheless a relatively fast process: in just a few years, the budding Kanada school had already its leaders, its main animators, and a flagship named Urusei Yatsura. This is a fascinating show, as it was such an important moment in anime history and saw some of the industry’s most talented creators meet. It started airing in 1981, the very start of the decade for which it would set most of the stage.

But what’s even more fascinating, and much harder to find material about, are the years that precede: roughly, between 1977 and 1983. Why 1977? Because that’s the year when Kanada (along with his friends Shin’ya Sadamitsu and Kazuo Tomizawa) flew the nest of Studio N°1 and created their own Studio Z2.

Although I don’t precisely know why they left, I’ve been able to piece together the chronology: Kanada was still working with Noda on Wakusei Robo Danguard Ace in April 1977, but his last two contributions to the show, in August and November of the same year, were without Noda. By July, Kanada and Tomizawa were already working on their own on Hyôga Senshi Gaislugger. It seems that Z2 was created during that in-between, in May 1977. Although Gaislugger was a Tôei show, my guess is that the studio must have been formed when Kanada and his friends decided to work for studios other than Tôei, most notably Sunrise. Their first collaboration would be on Invincible Superman Zambot 3, which started airing in late 1977.

Probably nothing more than a group of friends renting a place where they could work together, Z2 was short-lived, as a studio Z3 soon followed. It seems that the change was due to the quick growth of the structure: from the 4 initial members of 1977, there were already 10 people in 1978. This probably caused a change in location, as the studio would have had to rent a bigger place to house all of its members. But even then, Z3 disbanded as quickly: around spring of 1979, Kanada and many others left for another Studio N°1, yet again led by Takuo Noda

These details might seem uninteresting, especially since Z2-Z3 have been largely forgotten by nearly everyone. But it is notable, because it was the first birthplace of the Kanada school, and its aesthetic was very different from the style that emerged in the 80s. When you look at Z and N°1’s work between 1977 and 1982, what’s still very striking is Kanada’s overbearing presence. His rough lines and striking camera angles predominate, and it is only on the movies and opening sequences that Kanada and his students start developing newer and bolder techniques such as background animation and unique fire effects. This shows three things: how fast Kanada’s style evolved in his Z years, how quickly it took off, and how much the “Kanada style” of the 80s owes as much to one of Kanada’s first and most talented students: Masahito Yamashita.

The two young prodigies: Masahito Yamashita and Shinsaku Kôzuma

Kanada was just twenty-four when he created Z2, but its members were even younger, representing the newest generation that had been born in the late 50s or even early 60s. Osamu Nabeshima and Masakatsu Iijima, who were members of the original Studio N°1, did their first key animation under Z2 at twenty-one and twenty-two respectively; when Kazuhiro Ochi joined, he was seventeen, and the youngest animator in the entire industry. As for Yamashita, he joined the second Studio N°1 in 1980, at nineteen years old.

Yamashita represented yet another one of those meteoric rises: after just a few months as an in-betweener, he began key animating on the 1980 Tetsujin 28 anime, then the year after that was joint mechanical designer on Rokushin Gattai Godmars before making his definite breakthrough on Urusei Yatsura. By then, he had already left N°1 for another similarly small outsourcing stucture which he more or less led, Studio OZ. The cause of this is probably to be found in his own talent and Kanada’s lenience, but also in his strong sense of individuality: he was known for redrawing the in-betweens he was given to push for becoming a key animator.

The Tetsujin 28 series is fascinating, because Yamashita worked on it all along, and you can see him developing as it goes. At the very beginning, he was just a Kanada clone, and wouldn’t have stood out from the rest of the Z3 staff and their style: speed lines, slow timings and the extended limbs of the robots which feel like they’ve been drawn by Kanada himself. While the look is much cleaner, you almost expect the heavy black lines of 70s mecha and the rough explosions. But the 80s were starting, and the gekiga style’s direct influence was diminishing. You can see this in the effects: while their coloring is already somewhat unique, their motion is clearly modeled on the “liquid fire” kind of explosions Kanada had developed in Galaxy Express 999.

It was precisely in the effects that Yamashita first shone. The most noticeable aspect is the very heavy and distinct shading. Once again, it was but a wider application of something that Kanada had developed in Galaxy Express, but Yamashita made it systematic, with the result that stark shades would become a staple of 80s anime aesthetics. In that regard, it must be said that, whereas Kanada had been going in the way of more realistic mechanical animation, Yamashita took the opposite direction. Although meant to represent the gleaming aspect of metal surfaces, these shadows are heavily stylized and create visual motifs of their own, far from any kind of photorealism.

The same applies to the explosions, at the beginning and end of the sequence. If Kanada (and Yamashita himself, most of the time) was going in the direction of what I just called “liquid fire”—that is, very fluid motion and melting shapes—Yamashita introduced very angular flames and explosions. In the beginning of this scene, they go from round to rectangular to more triangular… and this happens on a very irregular and slow timing: it starts as low as 5s and goes up to 3s.

Finally, by the end of the series, Yamashita was pretty much on par with Kanada’s movie production, which was simply impressive considering that what the latter had done on Galaxy Express 999 and Terra E was already the peak of his career. Yamashita was consciously making direct references to it, as if to measure himself to his master, but was also innovating in every way he could.

On the left: Kanada; on the right: Yamashita

At the same time, another animator was starting to make the Kanada style his own: Shinsaku Kôzuma. He had started key animation at only nineteen, and at twenty did some in-betweens on Galaxy Express 999, although not on Kanada’s cuts. Kôzuma’s first years, before he met Yamashita, are interesting for two reasons: he very quickly went freelance, and while he is categorized as a Kanada-style animator, he wasn’t that much under his direct influence. Moreover, while most of the members of Z2 and Z3 started their careers on super robot shows and would stay associated with effects and mecha animation, Kôzuma began his animation career on magical girl and children’s shows: for the rest of his life, he would stay a character animator first and foremost.

In one of his earliest cuts, from Magical Princess Minky Momo in 1982, you already see how Kôzuma was going in the same way as Yamashita while already laying out the fundamentals of his own style.

In the first shot, the driver adopts a variety of ridiculous poses that any Kanada-style animator of the time wouldn’t have rejected; but what immediately stands out is the timing: we start on 1s, then proceed on 3s, then return to 1s and 2s. This is very irregular, but also makes a frequent use of higher framerates (1s and 2s). It would go on to become one of Kôzuma’s most used techniques. On the effects side of things, we can see how they were influenced by Kanada, but also how they weren’t: the different colors of the flames (yellow and orange) are separated by black lines, which makes them stand out that much more. That’s something Kanada had never done, preferring to let the colors interact freely with one another. Moreover, the explosion of the car at the end oscillates between redesigned Kanada-style effects (like the yellow lines that start popping up) and more classical, round shapes for the smoke.

Kôzuma and Yamashita had many things in common: inspiration, youth, originality and probably a bit of genius. It was a matter of course that they would eventually meet, and that they would create their own studio, OZ. This happened thanks to one of the most important series of the decade, Urusei Yatsura.

Oshii revolutionizes anime

Urusei Yatsura is probably one of the defining works of anime history at large, a central piece of otaku history, and the show that truly launched many of the stylistic and visual trends we still associate with “80s anime”. Its format—a long-running comedy series—placed it in the lineage of the great absurd A Pro comedies of the 70’s like Dokonjo Gaeru or Ganso Tensai Bakabon, and their descendants such as Doraemon. However, Urusei Yatsura differed from these on at least three points: its SF setting, its romantic comedy genre, and its parodic aspect. These were all the elements needed to cater to the burgeoning population of otaku and their sensibility for cool mecha, cute girls, and pop culture references.

In terms of production, the series was the directorial debut of yet another young visionary: thirty-year-old Mamoru Oshii. Despite many conflicts with the mangaka Rumiko Takahashi, he led the show in unexpected and experimental directions, and played a large part in giving the young Kanada-style animators a place to completely and freely express themselves, thereby largely contributing to the stylistic revolution that would take anime by storm. Along with him, the other major members of the staff who initially worked with the Kanada school were episode director Keiji Hayakawa and animation director Asami Endô.

Apart from some early exceptions like episodes 8B and 9B, it would be on 14A, one of Oshii’s episodes, that the Kanada school would make its first major mark. On the episode were two of Studio Z’s best alumni: Kazuhiro Ochi and Masahito Yamashita. Oshii’s fascination with machines and his frequent use of high and low angles were a perfect fit for the two men’s style, especially Yamashita who could go all-out with his unique metallic shading. It was also the moment when he really tried out what would make him so influential: lots and lots of weird poses that make the characters look like they’re dancing, off-model drawings with very long limbs, and a very exaggerated sense of timing.

Yamashita would quickly become one of the show’s star animators. One of his most iconic episodes was probably 29, when he went completely wild with background animation. It’s once again something Kanada had initiated, and Takashi Sogabe’s work on 8B was both the first instance of Kanada-style animation in the series and one of the first great background animation sequences of the Kanada school. But Yamashita is really the one who pulled out all the stops with endless running scenes full of wild camera movements, easter eggs and purposefully irregular run cycles. This would quickly become his trademark technique, and he would use it again many times on the series; legend has it that he even made some of his run scenes much longer than initially planned in the storyboards.

Yamashita quickly started bringing with him other staff from his Studio OZ, chief among them Shinsaku Kôzuma. As a proof of Yamashita’s overbearing influence, Kôzuma was uncredited and you can’t make out his style in those early episodes. However, this would quickly change, as episode 50 easily demonstrates. The characters are more off-model than ever, the movement is incredibly strange and fun with exaggerated perspectives and stretched-out limbs. But where Kôzuma really shines is in the effects, with tons of smears and an explosion at the end that’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen.

This episode, one of the best to which OZ contributed, came out in November 1982. By then the animation of the first Urusei Yatsura movie, Only You, would have been close to completion, since it came out in February 1983. It was there that the Yamashita-Kôzuma duo was at its peak, before Kôzuma would start going off on his own on Kaname Pro’s Plawres Sanshirô later that year. Yamashita was the mechanical animation director on the movie and really gave his all to the amazing dogfights in its second part. More generally, it was a big opportunity for more cartoony Kanada-style animators like Katsuhiko Nishijima, Hiroyuki Kitakubo or Yûji Moriyama; the latter would become joint AD for the second movie, Beautiful Dreamer, and one of the most important staff members of the latter half of the series.

While it’s hard to know how much he involved himself in the animation, Oshii’s role as a director was probably instrumental in the formidable animation powerhouse that Urusei Yatsura fast became. He seems to have quickly realized the expressive potential of the Kanada style and let its followers go free, trying his best to recruit them and have them work with him. This influence goes beyond the often very cool animation: the balance between the show’s comedy scenes and Oshii’s own obsession for vehicles and military hardware enabled the Kanada animators to really stretch their muscles in all kinds of animation, from effects to acting.

The progression of the Kanada style: the case of Motosuke Takahashi

Another interesting aspect of Urusei Yatsura is that it was not just a permanent showcase of Kanada-style animation. There are some great (and yet little known) animators of the early part of the show that never adopted the Kanada style, while some others only did so very slowly. That was the case for one of the most important members of the production, the one Oshii called “Pierrot’s trump card”: Motosuke Takahashi.

Takahashi, born in 1941, entered Tatsunoko Production in 1966. He was quickly put to work as key animator on the studio’s series such as Orâ Guzura Dado and Gatchaman, on which he quickly rose to become animation and episode director. After going freelance in 1975, he became a regular contributor on Sunrise shows and a frequent coworker of legendary super robot director Tadao Nagahama and character designer Yoshikazu Yasuhiko: he would be episode director and animation director on many episodes of Yûsha Raideen, Chô Denji Robo Combattler V and Chô Denji Machine Voltes V. In 1977, he debuted as chief director on Chô Super Cat Gattiger.

To put it briefly, he was already an important figure in the industry when, in 1979, former Tatsunoko employees created Studio Pierrot and asked him to join them. Instead of simply doing so, along with Asami Endô and Naoko Yamamoto he created his own 3-member studio which would exclusively subcontract for Pierrot: Dôtaku. The three of them would be among the most frequently-featured animation directors of the early part of Urusei Yatsura. Takahashi himself would contribute in a way or another to 20 episodes, with no less than 12 of them solo or mostly solo (he is credited with Naoko Yamamoto on most of them, but it seems like he did a large part of the animation himself and that Yamamoto did what amounts to second key animation). And it so happens that many of those episodes are among the craziest in the entire series.

The two fundamentals of Takahashi’s animation were fluidity and simplicity. He very much stood out in the landscape of early 80’s character animation, earning praise even from Hayao Miyazaki, thanks to his search for animation which would be as cartoony and fun as possible. This meant taking some liberties with the character designs, such as making their eyes unbelievably large or making characters’ heads bigger when they’re angry (something that would be overused and run into the ground after his departure, in the second part of the series). He was also one of the best storyboard and layout artists of the series, with a lot of small camera movements and movements in depth that emphasize the characters with a lot of nice little touches.

Two of Takahashi’s many silly faces

In terms of actual animation, he was as versatile as can be, with equal ability in nuanced, detailed moments of acting as in flashier and absurd sequences. In its most brilliant showcases, his style is a perfect counterpart to Masahito Yamashita’s. They both shared a similar love for long, extended limbs making wide, disarticulated motions, and had the same use of cycles, probably inspired by Kanada: slowing or accelerating them to make them interesting to watch. But Takahashi’s motion is more detailed: it’s on higher, less irregular framerates (this sequence, for instance, is mostly on 2s), with much closer spacings. In this cut, it creates a strange, maybe even uncanny, sense of fluidity, but it is always a resounding success in comedic climaxes.

Another similarity between Takahashi and Yamashita was their use of background animation in long and absurd chase sequences that could take up an entire episode—in this, I wouldn’t be surprised if Takahashi took some direct inspiration from Yamashita. In terms of chases, his masterpiece is undoubtedly episode 59, in which Ten constantly tries to run away from a persistent elementary school lover, while at the same time Lum chases Ataru all over town. As the episode progresses, Ten loses all composure until his very body becomes shapeless and completely consumed by the smears. The flow of the animation is spectacular, and the way it totally breaks loose from the character designs in order to create movement anticipates the work that one of Takahashi’s students, Atsushi Wakabayashi, would do a bit more than a decade later on Yû Yû Hakusho, in a very different register.

But strangely, rather than going further in that direction, Takahashi went in the opposite way: he started integrating aspects from the Kanada style, and his animation slowly grew more and more conservative. For example, while this sequence kept the sense of freedom and fun, the movement becomes slower in a typical Yamashita way, while speedlines start creeping up everywhere. They would be here to stay, and Takahashi’s animation became less interesting until he completed his transition to a director and storyboarder. After Urusei Yatsura, he would direct more Rumiko Takahashi adaptations that, while they aren’t exactly constant showcases of great animation, definitely showed that he had been won over by the now-dominant Kanada style.

And all the others…

It would be impossible to give to all the artists that participated in the Pierrot part of Urusei Yatsura the credit they deserve, but a few names must be mentioned. Among these are two categories. First, there are those who never adopted the Kanada style and whose work is a testament to the diversity and creativity of the series. The others are the direct or indirect students of the Kanada school, for whom Urusei Yatsura was but the first step in successful careers.

What’s interesting in the non-Kanada style animators is that the two most notable of them can be traced back one way or another to Yasuo Otsuka and the A Pro lineage. The first one is Katsumi Aoshima, an animator originally from studio Topcraft who would mostly contribute to Tôei series, notably Fist of the North Star and Dragon Ball. She did three solo episodes on Urusei Yatsura, which represent the early part of her career. What they show, especially the opening moments of episode 21, is a tendency towards cartoony and lively animation in the purest A Pro tradition: big, exaggerated expressions, wild poses and absurd visual gags.

The other notable name is Shôjurô Yamauchi, a name you’ll often find on many 80s classics: Sherlock Hound, The Dagger of Kamui, and The Legend of the Gold of Babylon. Although not very well-known, this ex-Oh Pro animator was one of the best members of Studio Telecom’s first generation, and a key asset on The Castle of Cagliostro. His presence in Urusei Yatsura is quite interesting and unexpected, although it seems he joined Pierrot for some time. While he contributed to Only You with some amazingly detailed acting sequences, his work on the TV series is notable for all the Miyazakisms you find in it: the characters in this scene look like they’re from Future Boy Conan or The Castle of Cagliostro, and these giant gears are bound to remind you something.

As for future big names who made their debuts or first major gigs on the series, you’re bound to recognize some if you’re a bit knowledgeable in 80s anime: Kazuaki Môri, Yûji Moriyama, Tsukasa Dokite, Takafumi Hayashi, Katsuhiko Nishijima, and Toshihiro Hirano… Among all of them, I’m mostly going to focus a bit on the last three.

Hayashi probably started as an animator at Pierrot in the early 80s, but he quickly joined Kaname Production, contributing as a key animator on Plawres Sanshirô and then as main animator on the studio’s three iconic productions, Birth, Genmu Senki Leda, and Windaria. However, it’s probably on Urusei Yatsura that he learnt most of the craft: he started animating on the series on episode 42 before becoming animation director on episode 73 and keeping the position for no less than 16 episodes, mostly on the second part of the show.

One of the most talented animation directors and key animators of the series, his speciality was highly deformed faces and expressions, while his use of smears and large motions sometimes made him look like Yamashita. His episodes are among the most fun in the series, and the incredibly strange way he drew Ten’s head is recognizable anywhere.

The second one, Katsuhiko Nishijima, is mostly remembered as the director of Project A-Ko, but he already had a rich career before that. After a failed attempt to join Sunrise in 1979 (as a nineteen-year-old fan of Mobile Suit Gundam, he apparently sent a letter directly to its director Yoshiyuki Tomino), he joined a series of small outsourcing studios until arriving at Deen, and then creating studio Graviton along with Hideaki Anno, Shôichi Masuo, and Kôji Ito.

He key-animated on 21 episodes of the series, in both the Pierrot and Deen parts. Just like Takahashi and Hayashi, he loved drawing characters with big eyes and having them adopt completely crazy facial expressions. His drawings had a thickness and power to them which were lacking in other animators’ work, but his real speciality was impact frames: he put them anywhere he could, and added, within them, many easter eggs such as A-Ko.

Finally, Toshihiro Hirano is probably the oldest and the most important of the bunch, whose later work in the 80s will warrant a whole separate article. Most notably, he was an alumnus of the original studio N°1, working alongside Kanada under Takuo Noda’s direction, and then joined studio Beebow, where he received more teaching from another legendary figure, Tomonori Kogawa. That’s where he met Ichirô Itano, who invited him to work on Macross. That was a crucial work in his career, as his animation direction on three episodes of Urusei Yatsura would very clearly bear the influence of Haruhiko Mikimoto in the shapes of heads, eyes, and eyelashes. Most notably, it was he who would bring in none other than Itano for a short but formidable contribution on one of the episodes he was AD for.

Here, I’ve only covered the first part of Urusei Yatsura, handled by Studio Pierrot, and I’ve only brushed its surface. As uneven as it could be in its writing, direction and animation, it was an incredibly rich, epochal series. Its success paved the way for many future trends, the Kanada style of animation among them. The incredible freedom the animators had enabled them to give some of their best performances, impressing both viewers and their colleagues. It was probably a formative experience for many of them, because thanks to it, they met many of their peers and made the connections which would ensure their success and continued careers for the rest of the decade.

Further watching:

Masahito Yamashita Urusei Yatsura sakuga MAD

Takafumi Hayashi Urusei Yatsura sakuga MAD

Katsuhiko Nishijima sakuga MAD

Complete staff credits of the Urusei Yatsura franchise ; translation and transcription by Jimmygnome and ibcf

Fantastic article, thanks for the informative read!

LikeLike