This is part 2 in the History of Mushi Production series. You can read the introduction here

While I’m hesitant to speak of “golden ages”, if Mushi Production had one, it was certainly the years 1965-1966. Still riding on Tetsuwan Atom’s prodigious popularity, the studio considerably expanded its personnel and activities. It launched production of new, ambitious TV shows, notably the first color TV anime, Jungle Taitei, and seemed to reach unprecedented artistic heights. But at the same time, the atmosphere at the upper level was getting worse, as Osamu Tezuka started realizing the situation was getting further and further away from what he originally envisioned for Mushi, and the anime industry knew its first deaths. Mushi’s success was not just built on the vision of ambitious and passionate creators, but also on frustrations, failures, and human lives.

The two years I will cover in this article are remarkably dense. For this reason, I will not follow the events in chronological order. To make things easier to follow, I will first retrace the studio’s development from a pure business perspective, before focusing on its two new productions, W3 and Jungle Taitei. While the latter seems to have entered planning first, I will cover it last as it started and ended airing later. But it remains important to keep in mind that all the events I’ll narrate here happened simultaneously, keeping all those who left through them extremely busy and, perhaps, disoriented.

The new Mushi

Mushi’s expansion

By Fall 1964, Mushi Pro counted 230 employees, half of whom were busy on Tetsuwan Atom [1]. In December, as the studio started planning its two next TV series, the staff shortage became apparent: a new recruitment campaign was launched and, between September and December of the same year, 157 new people entered. Itô and Nagao provide a precise list of their positions: 26 people in the production section, 1 in literature, 11 in direction, 17 in animation, 25 in backgrounds, 19 in ink, paint and special effects, 8 in photography, 3 in editing, 1 in recording, 3 in materials, 12 in management, 2 in sales, 2 in publishing, and 27 in other tasks [2]. In 1965, another 117 people joined and, in 1966, 112 more [3]. Accounting for the departures, according to Tezuka, Mushi peaked at 550 employees [4]. While I don’t have the numbers for Tôei at the same date, it’s probable that by this point, Mushi Pro was the biggest animation studio in Japan.

This spectacular growth might make it seem like Mushi, always hungry for new staff, recruited quickly and easily. Nothing could be further from the truth: probably from the first public recruitment campaign of September 1963, entrance in the studio was conditioned by success on an exam and interview. And, at least for animators, this process was particularly difficult: all the people who remember it recount hundreds of participants, out of which often less than ten were selected in the end. Some, like Kazuhiko Udagawa and Ryôsuke Takahashi, had to pass it twice [5]. Osamu Dezaki would have failed if not for Gisaburô Sugii’s last-minute intervention [6]. Many other future Mushi talents such as Akihiro Kanayama or Yoshiaki Kawajiri only entered through personal recommendation. The same Kanayama also mentioned that two future legends of manga and anime, Monkey Punch and Kazuo Komatsubara, failed to pass the exam [7]. As for the contents of the exam, they seem to have consisted of various drawings and animation tests, such as animating Atom lifting a barbell (surprisingly similar to Tôei’s entrance exam) or Leo running [8]. The interview does not seem to have required a portfolio examination, though many people brought theirs when they had one.

This expansion in personnel called for an expansion in locations. By that point, Mushi counted 3 studios. In 1965, it acquired two more: in August, studio 4 started operations on the second floor of an apartment located less than a minute’s walk away from studio 3. It mainly served as a meeting place for members of the business and directors’ divisions. Then, in November 1965, a disaffected school 10 minutes away from studio 1 was rented and became Mushi Pro studio 5. It would serve as the working place for all of Mushi’s outsourcing partners, such as Art Fresh or Fantasia. Moreover, in July 1966, the management and publishing sections were moved closer to the heart of town and to business partners, respectively in Ikebukuro and Shibuya [9].

A map of Mushi’s studios [from Itô & Nagao 2004; walking distances have been added by me]

COM and the modern dôjinshi scene

The publishing department was an important part of the company, and made the link between Tezuka’s anime and manga activities. It initially counted 2 members, Kuniyasu Yamazaki and Kotoko Sakurai, whose task mostly consisted of editing the Tetsuwan Atom Club magazine [10]. By late 1966, their work suddenly expanded as Yamazaki was assigned chief editor of a new magazine, COM, the first volume of which came out in January 1967. COM’s creation was decided for both artistic and financial reasons. Tetsuwan Atom Club didn’t sell well and Mushi’s publishing department was in the red; moreover, it ended publication with Atom’s run in December 1966 [11]. A replacement was needed both to take its place and improve the finances.

On the creative side, COM was Tezuka’s answer to the development of arthouse manga notably pioneered by Garo since 1964. On one hand, it served as a base for experimental manga, such as Tezuka’s Hi no Tori or Shôtarô Ishinomori’s Jun, which contained almost no dialogue and was only carried on by its art. With time, it would also publish some of Garo’s artists such as Shigeru Mizuki and Yoshiharu Tsuge, or some more of Tezuka’s friends such as Fujiko A. Fujio and Leiji Matsumoto. On the other hand, it served as a platform for Tezuka to reaffirm what he stood for, “story manga”, against the combined attacks of gekiga and arthouse manga. In his first editorial for COM, Tezuka wrote that the magazine would “display the true meaning of story manga” [12].

COM was fully a part of Mushi, and contributed to give it an identity distinct from other studios. For one, it naturally included many ads and columns dedicated to the studio’s productions. Moreover, it published the work of some of Mushi’s artists – such was the case of Osamu Dezaki, who wrote a manga version of Goku no Daibôken in 1967, or Moribi Murano and Shinji Nagashima [13]. Finally, it also deepened the symbolical antagonism with Tôei, whose artists – notably the union members gathered on Hols, Prince of the Sun – were rather avid readers of Garo and ardent fans of its lead author, Sanpei Shirato [14].

Ads for Mushi’s works in COM: Ribbon no Kishi, Goku no Daibôken, Vampire and Wanpaku Tanteidan. [From here ]

This was not all: as Tezuka himself stated in his opening editorial, “COM” stood for “comics”, “companion” and “communication”. Tezuka addressed his editorial to his “fellow lovers of manga”, and one of the magazine’s catchphrases was “a magazine for the manga elite” [15]. COM’s editors’ team was well aware of the context of the manga industry, a so-called “manga boom” in which prepublication magazines were becoming the overwhelmingly dominant format and new categories such as gekiga and arthouse works appealed to a wider, older audience of university students and adults [16]. Their answer was to focus as much as possible on the two last keywords at the origin of the magazine’s name – “companion” and “communication”.

One could say things happened mostly by chance. In late 1966, Yamazaki and Sakurai, the magazine’s two editors, found themselves short of 30 pages for the first issue. They asked the advice of Mushi producer and mangaka Masaki Mori, who suggested creating a readers’ submissions section. Yamazaki and Sakurai took his advice, and assigned Nobuaki Ishii and him editors of this section (Mori would publish under the alias Akane Tôge). This was the birth of Gura-Con, short for “Great Companion”, and one of the most important events in Japanese manga and fandom history [17].

Gura-Con initially operated in quite a simple manner: COM received manga submissions, one of which would be selected by Ishii and Mori for publication each month [18]. However, the Gura-Con team, which grew in number, soon expanded its activities to reviewing and teaching manga writing and drawing techniques. With time, COM became one of the leading publications in manga criticism and theory, with a series on foreign comics written by Kosei Ono, a news section dedicated to manga and anime by Shin’ichi Kusamori, a column called “Manga and me” featuring contributions by mangaka, actors, film directors, writers… and criticism and theory articles with titles such as “Is Manga Art?”, published in March 1968 [19].

Gura-Con itself, as a separate section, became the most important platform in Japan for aspiring manga artists. Among the ones who debuted in it were two of shôjo manga’s most important artists, Fumiko Okada and Keiko Takemiya; but also some of those who would define 70s and 80s manga, like Daijirô Morohoshi, Katsuhiro Otomo and Mitsuru Adachi. While they don’t seem to have been published in it, others who took part in Gura-Con and the amateur manga scene of the time included Monkey Punch and Hideo Azuma. Gura-Con’s role was not only to highlight new artists, but also provide a platform for all amateur artists in Japan – through it, COM effectively gave birth to Japan’s modern dôjinshi scene.

Two Gura-Con related publications: the first volume of a submissions anthology (left) and the official magazine of the Kansai branch of the Group Gura-Con (right) [from here]

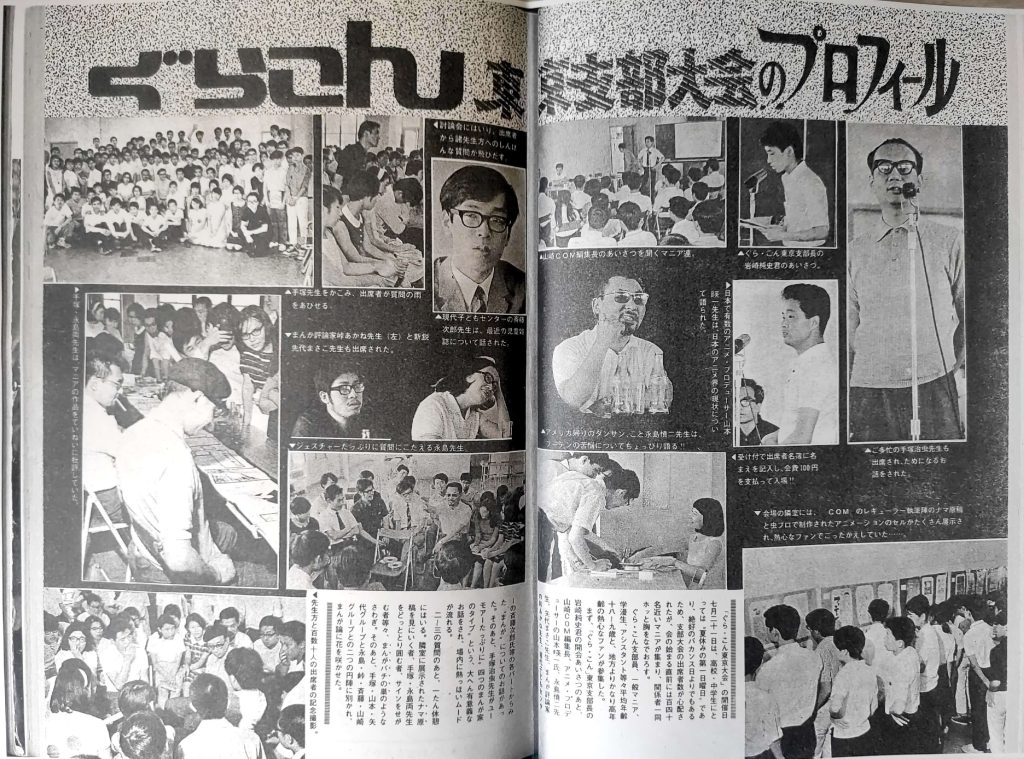

In March 1967, “Group Gura-Con” was created, with the ambition of providing “a gathering place for all manga maniacs in the country” [20]. Divided in 9 regional branches which sent their submissions to the magazine, it centralized most of the amateur manga groups in Japan in a single organization. These dôjinshi groups, not yet called circles, had existed in isolation since the end of the war and suddenly found themselves in contact with each other and with a direct access to magazine publication [21]. Things didn’t only happen by letters and magazine submissions: on August 21, 1969, the first “Group Gura-Con Tokyo Branch Festival” took place in Tokyo, gathering “140 maniacs” – most of them between 18 and 20 years old. COM chief editor Yamazaki, Mushi producer and director Eiichi Yamamoto, multiple mangakas and Tezuka himself also attended and gave lectures. Such events happened all throughout the country.

The report of the 1st Gura-Con Tokyo Branch Festival, from the September 1969 issue of COM

Following a change in chief editor in 1969 and Mushi’s increasingly fast decline, COM also found itself in trouble. It stopped publication a first time in December 1971 and then definitively in 1973, and Gura-Con disappeared with it. In the early 70s, many attempts were made to protect or revive its network, such as the attempted “Gura-Con Information Center” in September 1971, which intended to maintain direct contact between all the regional sections, or the amateur magazine Mangajuman, which stopped after 3 issues [22]. It wasn’t until December 1975 that some of Gura-Con’s former members and contributors finally managed to create a stable structure to coordinate their activities and gather dôjinshi artists from all over the country: this was the Comic Market, which remains to this day the most important event in otaku culture [23].

The Anami system

By the time COM started publication, Mushi’s publishing division was not really part of Mushi anymore – or rather, not part of Mushi Production proper. In Summer 1966, Mushi’s Managing Director and chief of the Sales division, Kaoru Anami, initiated a complete restructuring of the company. Anami seems to have perceived the situation as follows. The main reason Mushi’s TV series were not in the red was because they were sold overseas – this applied to Atom, W3 and Jungle Taitei. However, Anami wanted Mushi to be completely self-sufficient and carry on just thanks to the budgets negotiated with TV stations and merchandising. But he also knew that achieving this required careful planning and acute business sense, things that were lacking in Mushi as a whole and Tezuka as an individual. In order to realize his goal, Anami therefore launched three projects.

First, he wanted to gather all of Mushi’s staff in one place. With Tezuka’s agreement, he started planning the construction of a monumental studio built by famous architect Kiyonori Kikutake, meant to be located in either Tama or Komae, two areas on the outskirts of Tokyo which were going through major urban development at the time. Second, near this new studio, he laid out plans for “Mushi Pro Land”, a theme park inspired by America’s DisneyLand [24]. These would be funded by fundamental changes in Mushi’s structure.

First, the studio’s accounting was reviewed from the ground up and the finances completely restructured. Then, on September 1st, 1966, the publishing and copyright/management divisions split off from Mushi Pro and were absorbed into a new company, Mushi Pro Trading, directed by Tezuka’s manager Yoshiaki Imai [25]. This new entity also took on all of the animation studio’s debt, which is said to have amounted to 150 million yen, and started paying it off at a quick pace thanks to the merchandising rights it got from Tezuka’s IPs [26]. Anami’s goal in dividing Mushi’s activities was clear: it was to separate the production and the business sides so that they wouldn’t interfere with each other and to thoroughly clean up Mushi’s finances. From that point on, Mushi Pro would only have to handle the budgets it received for TV shows, while all other activities were in Mushi Trading’s hands. While it seems that Trading took on the planning of some animation series and the negotiation with sponsors, Mushi Pro remained the parent company [27].

At the core of this new organization was one individual, Kaoru Anami. He was second only to Tezuka, and effectively handled all the communication between Mushi Pro and Mushi Trading. According to Eiichi Yamamoto, these changes were known as the “Anami System” within the studio [28]. Anami obviously had great ambitions for Mushi, and led the company in such a way that Tezuka, too busy and too inexperienced to take care of business himself, would remain a creator and a figurehead. But it seems that Tezuka himself was unhappy with the changes. According to Yoshiyuki Tomino, he uttered words he could not go back on, saying “this isn’t my Mushi Pro anymore” [29]. Even more significantly, during a general assembly on October 11, 1966, Mushi’s president called for the opinion of all employees in the following terms:

“I would like to hear the thoughts of all employees regarding the direction Mushi Pro should go from now on:

1) Be a group of artists aiming to create works with an artistic character

2) Be a company with a salaryman spirit working at an industrial pace” [30]

According to Yamamoto, “most of the 400 or so employees in Mushi could not understand Tezuka’s intent, and their only answer was perplexity” [31]. Put more bluntly, it seems that a number of Mushi’s new employees – especially in the production and direction departments, who had to bear with Tezuka’s chronic inability to meet deadlines on a daily basis – increasingly came to see the mangaka as a hindrance to the good functioning of the company. While I don’t know the precise answer Tezuka got, it is clear that his attempted resistance – or coup? – ended in failure. The studio would keep making experimental works, but Mushi Trading would have no part in them, and the mangaka would have to fund them himself [32]. As Yûsuke Nakagawa wrote, Atom “had given birth to the monster known as TV anime. And its creator, Osamu Tezuka, had lost all control over it” [33].

From Number 7 to Wonder 3

From the point the Mushi Pro Land TV series had been dropped in early 1964, the main staff of the studio had been looking towards their next project, Mushi’s second TV series. With the Tokyo Olympics in October 1964, it wasn’t just TV as a media that was on the rise: color TV quickly developed and would soon become dominant [34]. Sometime in early 1964, a color adaptation of Jungle Taitei was approved, which would be in the hands of Eiichi Yamamoto; then, in May, the Mushi Pro Land team was transferred to Mushi’s planned third series, Number 7 [35]. Quite incomprehensibly to me, Yamamoto says that Number 7 was planned at the same time as Mushi Pro Land (that is in late 1963), meant to be in color, and directed by Yûsaku Sakamoto whereas Land was directed by Sugii (he was only animation director on the one completed episode) [36]. The only explanation I can give is that Yamamoto confused the two projects.

In any case, Number 7 would have been an adaptation of Tezuka’s manga of the same title, which had run between 1961 and 1963 in the magazine Hi no Maru. This SF action series followed a group of special agents fighting aliens and mutants on a future Earth devastated by nuclear war. However, the project was quickly dropped. The official reason was that, around the same time, another studio had started planning a series with a similar team dynamic – in all probability Studio Zero and Tôei’s Rainbow Sentai Robin [37]. However, another reason seems to be that mutants and nuclear apocalypse were subjects considered too sensitive to be the main themes of a children’s program. Aritsune Toyota seems to imply that conflict ensued between Tezuka and Sakamoto over the issue, leading the latter to leave his position as chief director [38].

The ideas for the first Number 7 were then recycled in various ways: some of its plot elements were put into episodes of Astro Boy, while the character drafts were reworked for its replacement. Under the same title, it transformed into a spy story inspired by the 007 series in which hero Kôichi would be assisted by a telepathic squirrel named Bokko. It is as planning was well underway, in the first months of 1965, that the so-called “W3 incident” began. A new Number 7 manga by Tezuka was meant to be published in Shônen Magazine, but on January 5th, 1965, the mangaka suddenly announced that the deal was off [39].

At the same time, rival studio TCJ was planning its own new series, Uchû Shônen Soran, which would start coming out in May 1965. Its mascot character, telepathic squirrel Chappie, was suspiciously similar to Number 7’s Bokko. Plans for Number 7 had already been changed once, but this uncanny resemblance was too much for Tezuka, who snapped. Convinced that an “industrial spy” had leaked Number 7’s settei to TCJ, he ordered a thorough investigation inside the studio, and set his sights on a perfect culprit: Number 7’s chief writer and regular TCJ collaborator, Aritsune Toyota [40].

Sadly, the only direct testimony of the events that I know of is Toyota’s, making it very difficult to tell how things really happened. Moreover, he told the story in multiple instances, with small variations each time, so caution is in order. In any case, recouping Toyota’s retellings, what happened seems to be as follows. Tezuka first gathered all of Mushi’s section chiefs to tell them about the “industrial espionage” case and his suspicions about Toyota. Writing department chief Arashi Ishizu seemingly took his colleague’s defense, to no avail [41].

Then, Tezuka called Toyota and Ishizu to his office, and immediately started accusing Toyota, almost insulting him – an extremely unusual behavior for someone whom every testimony describes as affable and well-mannered [42]. It seems that the meeting ended with Tezuka demanding Toyota to “leave this company this instant”. Ishizu apparently remained silent the whole time. Toyota left the room, packed his things and never went to Mushi Pro again – what few scripts he wrote for the studio afterwards were done without Tezuka’s knowledge, and only as a favor to friends. Ishizu left the studio soon after.

In all versions, Toyota claimed his innocence. In my opinion, there is no reason not to believe him on this: his first testimony dates from almost 40 years after the facts and 21 years after Tezuka’s death. It doesn’t seem like he would have any significant reason to lie. Moreover, his explanation that he was so busy on Atom that he stopped working for TCJ until he was kicked out of Mushi sounds reasonable. But then, what happened? To my knowledge, three explanations have been offered, all equally convincing.

First is Toyota’s. He claimed that “a certain writer” working with TCJ, to whom Tezuka had asked their opinion about Number 7, shared Mushi’s projects. According to Toyota, this individual, whoever it was, “had no bad intentions” but just acted as a SF fan passionate about this new plan and never had any intent to “sell” any secrets [43]. Next is Reito Nikaidô’s hypothesis, which is that planning documents circulated a lot between advertising agencies, TV stations and sponsors, and that it is probably as a result of this that Mushi documents themselves either ended up in the hands of a TCJ-related producer, or that they heard about the project [44]. In these versions of events, there was indeed a leak, however unintentional. Finally, Yûsuke Nakagawa provides a far simpler answer: from early 1964 onwards, Mushi Pro’s publishing department had started putting out calendars featuring Tezuka’s characters. The 1965 edition, released in late 1964, apparently featured an illustration of Number 7 main character Kôichi and Bokko – these calendars would naturally have circulated within the anime industry, and any TCJ artist could have used them for inspiration [45].

A 1968 ad for Mushi Pro calendars from COM

If this is indeed what happened, what these events indicated more than anything was Tezuka’s pride, state of complete exhaustion and paranoia. In particular, Tezuka’s accusations of “industrial espionage” were completely out of line. Hadn’t he heard about Rainbow Sentai Robin more than a year before it aired and seen Soran‘s settei months before it started? The truth was that the anime industry was extremely small, and that people and information circulated all the time. People came and went as they pleased. W3 producer Atsushi Tomioka even claimed he went to Tôei and TCJ to “study their production systems” while editor Tadashi Furukawa visited Tôei during the production of Wolf Boy Ken to study their techniques of editing – if anything, this was closer to industrial espionage [46].

Moreover, the fact that nobody in Mushi was able to appease Tezuka or remember the calendars issued just a few months ago (if this is what happened) is a worrying sign. The arbitrary accusations against Toyota and his sudden departure must have considerably soured the atmosphere in Mushi and played a large part in the slowly growing animosity many felt towards the studio’s president.

The successive versions of Bokko’s designs. From left to right: Number 7 drafts, first draft, W3 pilot, final version [Tezuka 1999b]

Things didn’t end there. Number 7 became Wonder 3; the spy Kôichi turned into the older brother of main character Shin’ichi, Bokko became a rabbit and was given two new comrades, horse Nokko and duck Bukko. A pilot film was produced and the airing date was set on June 6, 1965 on Fuji TV. In March 1965, Tezuka started publication of the W3 manga in Shônen Magazine. However, it was discontinued after 6 chapters: Tezuka was told that Soran’s comicalization would soon start in the same magazine. Still not calmed down, Tezuka made the following demands to Shônen Magazine’s editors: either they canceled Soran’s publication, or he would stop working on W3. The details of the talks are unclear, but the editors did not follow suit, perhaps pressured by Morinaga, which sponsored both the magazine and Soran. Tezuka executed his threat, accusing the editors of having tricked him and stopping any collaboration with publisher Kodansha until 1974 [44]. At the same time, one of Shônen Magazine’s most popular series, Kazuhiko Hirai and Jirô Kuwata’s Eightman, stopped publication, leading to a sudden drop in sales and to chief editor Shûji Ioka’s resignation. The W3 manga would start anew in a rival magazine with which Tezuka regularly worked, Shônen Sunday.

W3 and the Tezuka faction

Number 7, which took the succession of Mushi Pro Land, was meant to be produced in Studio 3 and directed by Yûsaku Sakamoto, presumably seconded by Gisaburô Sugii. However, Sakamoto left and began work on what should have been an original Atom feature film, which never saw the light of day [45]. Sugii, having left for Art Fresh, went back to TV Atom. In their place, Tezuka intended to assume chief direction himself, but couldn’t dedicate himself fully to the task: he was, after all, still supervising all of the scripts and storyboards on Atom on top of his manga [46]. He therefore sought the help of former Tôei animator Taku Sugiyama. Sugiyama would be credited as “chief director” and Tezuka as “sô kantoku”. It is around this time that Sugiyama invited his sister Yôko to Mushi – she would enter the ink & paint department and, years later, create studio Kyôto Animation with her brother and her husband Hideaki Hatta [47].

By the time Sugiyama arrived, a contract had already been signed and the airing date of June 6th, 1965 settled [48]. He was therefore not involved in the production of the 15-minutes pilot film, storyboarded and perhaps animated by Tezuka. Narratively, it stands between the second version of the manga (I couldn’t read the first and ascertain its contents) and the finished first episode. Its pacing and direction are awkward, but the most striking is the extremely low quality of the animation. This pilot barely moves, and what few action or acting scenes there are rely exclusively on holds and pull-cels. This apparently satisfied Fuji TV and the sponsor Lotte, but I doubt that Tezuka, for whom movement was the fundamental aspect of animation, was happy with it. This was probably caused by W3’s severe lack of staff: according to Eiichi Yamamoto, only 25 people were available in the studio to work on it [49].

Although it was extremely reduced, W3’s staff was chosen carefully. Tensions were spiking within the studio and Tezuka gathered around him only the people he could trust the most – often young artists who looked up to him and didn’t have the ambitions and rebellious spirit of Mushi’s first generation of directors like Yamamoto, Rintarô or Sugii. The mangaka found many ways to cultivate loyalty: for example, he gathered young staff, asked them what position they wanted to occupy and gave it to them. This was notably the case of Ryôsuke Takahashi, a production assistant to whom Tezuka initially offered sound direction; but, when Takahashi told him he preferred to direct, Tezuka gave him a place in the direction rotation [50]. Moreover, Tezuka regularly held a workshop for the W3 team, teaching them techniques of writing and direction, thus bringing them even closer to his own individual vision [51]. Another factor in the selection was physical and psychological strength: W3’s planning had been extremely difficult and the show began production on short notice, meaning that it needed staff able to bear the workload and the coming hours of overtime and all-nighters [52].

Outside of Tezuka’s close but restricted circle, most of W3’s animation was outsourced, though I can’t tell to whom exactly in the absence of full credits. Tezuka animated on the show himself, doing keys and in-betweens here and there, but most notably animating Bokko’s transformations. This was both the poison and the cure: Tezuka did animation to compensate for the lack of staff, but as he always delivered his cuts late, he only made the schedule worse. The mangaka also asked for the help of two of his closest and most talented friends. The first was Kazuko Nakamura. When her husband Kaoru Anami entered Mushi Pro in July 1963, she resigned from the company to work as a housewife, perhaps to follow Anami’s wish, but also perhaps to avoid any accusations of favoritism within the company – not only was she married to one of the company’s executives, she was extremely close to Tezuka [53]. Probably urged on by both men, she came back to serve as animation director on W3. The second was Sadao Tsukioka, who had by that point quit Tôei and worked as a freelance animator. On W3, he would serve as scriptwriter, episode director, and most probably animator.

With two Tôei alumni having such important positions on the show, it was natural that others would follow. Mushi played its trump card by inviting Tôei ace Yasuo Otsuka and having him animate the opening. The circumstances that led to it are famous and have been told by Otsuka himself: he took the Anami couple’s car on a test drive only to crash it; for compensation, Anami asked him to work on the W3 opening. It reportedly took him one month to complete [54].

The car crash is a typical Otsuka story, but it didn’t always take such circumstances to make him work with Mushi. From Otsuka’s own testimony, he was on extremely good terms with Tezuka, who had offered him to join Mushi back in 1962. Gisaburô Sugii also said that he called his mentor on whenever a scene was particularly complex or required a lot of movement. He returned the favor by occasionally moonlighting for Tôei, such as on Kaze no Fujimaru [55]. Sugii notably gives the example of Vampire, a 1968 TV series mixing live-action actors and animated animals. Although Sugii is credited as animation director, he never attended any meetings or did anything more than layouts – all of the 2D parts, from the designs to the animation, were done by Otsuka [56]. As we will see later on, some Tôei animators worked with Mushi on the Animerama films: although unofficial (Tôei’s artists were never credited), the contacts were extremely frequent.

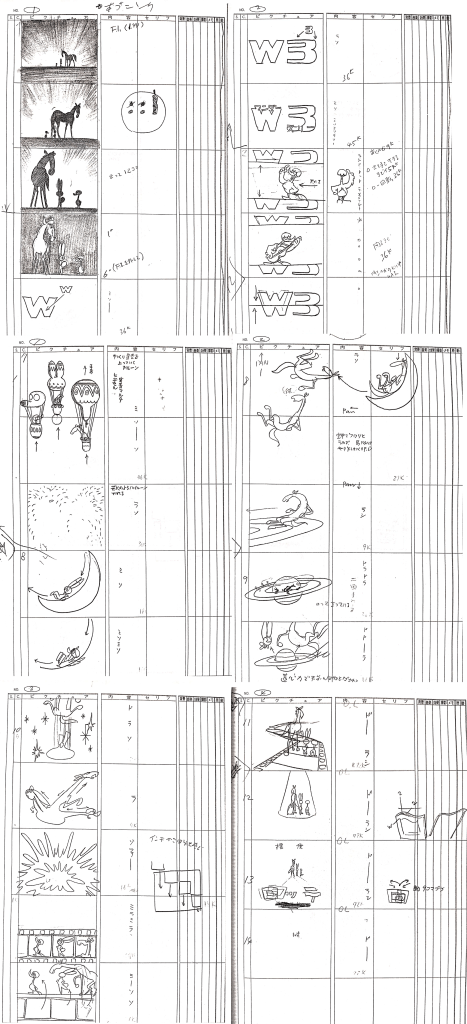

Tezuka’s storyboard for the W3 opening

Because these collaborations were so normal, I don’t think it’s possible to frame W3’s opening as a sort of exception, where the Tôei and Mushi styles of animation were put side-by-side and their huge differences exposed. Tezuka’s storyboard was as lacking in detailed instructions as ever, but he still closely supervised it, using framing techniques reportedly inspired by Saul Bass and insisting that the timing of the animation should be perfectly matched with the music [57]. Otsuka’s use of 2s (though he’d modulate things) perfectly fit the order, while corresponding to the cinematographic and meta dimensions of the opening. Bokko, Nokko and Bukko feel incredibly three-dimensional – which is helped by the rotations and circular movements planned in the storyboard – just like performers parading. Certainly, the aesthetic of the opening is completely different from that of the show, but calling this exceptional would be ignoring how anime openings work in the first place.

On Tezuka’s idea, W3 adopted a unique system for its animation [58]. As I mentioned, most of it was outsourced, but animation direction was done in-house and divided by characters: Nakamura, who had always specialized in animating girls, was in charge of Bokko; Shingo Matsuo did Bukko, and Takateru Miwa Nokko. They would occasionally work on the guest characters, but it seems that those were mostly handled by Nobuo Onuki. On top of this, while it seems that character designs were done by Tezuka, the way they were drawn differed a lot from Mushi’s other works, both Atom and Jungle Taitei.

First, the outlines are remarkably thick, creating a graphic look. In moments in which the movement was most stiff, such as the pilot (or the sequences reused from it), it even feels like the animation is made in paper cutouts. This is especially the case for Kôichi, whose design is all straight lines and angles, making him stand out from other characters. Second, shading was systematically used, especially on closeups, to create a sense of volume. Atom had sometimes gone in that direction despite its limited color palette – only 7 shades of gray according to Eiichi Yamamoto [59]. W3, which seems to have used the same gradation, refined its use even further. While I don’t know if there were any other reasons for these two aesthetic choices, it’s also possible they were inspired by other series made outside of Mushi – Eightman, in particular, had extremely strange designs whose uncanniness partly comes from the remarkable sense of volume with which they were drawn.

Shading and thick outlines from the W3 pilot

W3’s actual animation is a clear improvement compared to the pilot, but it ultimately rests on the same principles: stiff pose-to-pose movement made dynamic by pull-cels, repetition of cycles on low framerates – a technique often used to comical effect – and extremely fast editing. This was imposed by the aforementioned lack of staff, as well as an extremely low budget and tight schedule – Sugiyama reports that he never came home during the production and that, just like Tezuka, he had to do animation himself [60].

But, in a 52-episodes series, one can naturally expect some level of diversity. Frame-consuming techniques such as background animation make regular appearances, as they actually do in most 60s anime. What is perhaps more surprising is the occasional but undeniable work on effects animation, notably lightning or liquid, animated on 1s and 2s and then repeated in cycles. Effects were still very much used as stock footage, but they weren’t the completely undifferentiated, anonymous thing they were on Atom or in many series by other studios. The character animation also sometimes manages to extract itself from the pose-to-pose aesthetic, perhaps due to Nakamura’s contributions – Bokko’s acting in the early episodes is the best in the entire series and no doubt due to her – and to Tsukioka’s – although his episodes do not feature the extremely high level that could be expected from the one who had animated most of Wolf Boy Ken by himself.

If the animation is uneven and sometimes awkward, it is instead in its writing that W3 works. This isn’t the case for all episodes, but those which focus on Kôichi and his spy activities, which are probably the ones closest to the original Number 7 plan, feel like mini-007 films and are always entertaining. But these episodes are pulled down by the other, more clearly child-oriented ones, in which Shin’ichi and the Wonder 3 are the focus. Paradoxically, the three titular characters are the least interesting part of the show.

Tezuka must have been bitterly aware of this. The W3 manga is one continuous narrative, full of twists characteristic of the mangaka’s writing. However, this was impossible to realize in animation: probably on the request of Fuji TV in Japan or NBC in the US, the stories were kept episodic. This posed no problem on something like Tetsuwan Atom, which was divided in relatively independent chapters, but for something like W3 – or Jungle Taitei, as we’ll see – this actually went against the show and Tezuka’s original intent to do “story anime”.

The differences between manga and anime did not just apply to narrative structure, but also to character development. In the manga, Shin’ichi is a charismatic character, whose uncompromising righteousness makes him unfit for the society around him. His arc precisely consists in improving himself morally and physically while earning the love and respect of those surrounding him. In the anime, all this is erased by the episodic structure, and Shin’ichi just becomes another good kid helped out by his animal sidekicks.

Eiichi Yamamoto’s producer system

Whereas Atom and W3 were under Osamu Tezuka’s constant supervision, Jungle Taitei was Mushi’s first work to be done completely outside of the mangaka’s control. It seems that this was actually imposed on Tezuka by the rest of the studio – Ryôsuke Takahashi just says it was Jungle Taitei’s “staff”, while Keijirô Kurokawa implied it was Eiichi Yamamoto himself who asked Tezuka to stay out [61]. Whoever had the idea, it could certainly not have been put to effect without Yamamoto and Anami’s approval, as they were the only ones in the studio whose voices were strong enough to veto Tezuka in such a way. Under their hands, Jungle Taitei was the occasion to start things anew and try out a completely different production process: without Tezuka there to put the schedule off the rails, things could progress smoothly, slowly, and meticulously.

As mentioned above, discussions for Jungle Taitei started as soon as the Mushi Pro Land series was dropped, seemingly around February 1964 [62]. It was planned to be in color from the start, but that entailed much higher costs than other series. On Anami’s suggestion, it was decided that Jungle would be sold to NBC Enterprises in the US before any deal would be concluded with Japanese partners. A contract was signed for 52 episodes sold at 20,000 dollars each – if exchange rates had not significantly changed since the Atom deal, that meant around 7 million yen [63]. The series was then sold to Fuji TV at a price of around 5 million yen per episode. The sponsor was Sanyo Electronics, who intended to use the show to promote its new line of color televisions. However, it seems that Yamamoto saw very little of that money: perhaps in agreement with Anami, he settled on a budget of 2.5 million yen an episode [64].

These negotiations had a direct effect on Jungle: NBC had three conditions for buying the show. One, it should not be a continuous narrative, but completely episodic – NBC planned to shuffle the episodes and not air them in order. Two, human violence against animals should not be depicted. Three, black people should have as little onscreen presence as possible [65]. Taken out of context, the latter may sound like a blatantly racist request but, according to both Yamamoto and Tezuka, it was actually the opposite. Here is how the former explains it, through Anami’s mouth (Tezuka provides pretty much the same quote): “It’s a big issue there. If you absolutely have to include black people, they mustn’t be the villains. All the bad guys must be white. Moreover, when you draw them, they mustn’t be in the cartoony style of the manga, but drawn realistically. The most important is, don’t make the lips too thick” [66]. This was, after all, in the middle of the civil rights movement, and NBC probably wanted to avoid the caricatural blackfaces that were so frequent in manga and anime at the time (see, a few years later, Tôei’s Cyborg 009).

Whatever the reason, these demands put huge constraints on Jungle Taitei from its very inception. All three basically contradicted the core identity of Tezuka’s original work, something that the mangaka would not forgive, seemingly blaming it on Yamamoto: he would call him after the broadcast of each episode to complain that this “wasn’t his work” [67]. Still, the deal was on and the producer had to make do with the situation he was in. He therefore spent most of 1964 laying out the general development of the show and the plot of each individual episode, assisted by Masaki Tsuji, who became Jungle’s chief writer and assembled the scriptwriting team [68]. Tezuka was largely kept out of the process, but he made one suggestion: the first 52 episodes should be focused on Leo’s childhood, and then a continuation would be made focusing on his adulthood. Considering Atom’s success, it seems like he naturally expected Jungle to last for at least 2 years.

All this took time. It wasn’t until a general assembly on January 4th, 1965 that Jungle’s production officially started and that the staff repartition between Mushi’s three studios was concluded. In studio 1, 80 people would remain on Atom; in studio 2, Jungle would gather 115 employees; the remaining 35 were transferred to studio 3 to work on live-action and CM projects, and soon W3 [69]. Yamamoto selected Masami Mori as his assistant producer and together, they drafted a precise organization chart, schedule and budget, planning all of the show’s accounting during the entire year it would run. The idea was to plan everything in advance so that no incident or delay would ever occur – which incurred opposition from many people in Mushi, from the accounting division to Tezuka himself [70]. But, just as Tezuka gathered and trained his followers around him on W3, Yamamoto wanted to get people on his side: he gathered all of Jungle’s staff together to convey to them the circumstances and goals of Jungle Taitei’s production and the motto “let’s make something good quickly, cheaply and happily”. According to Jun Masami, one of the meeting’s participant’s reaction was “I didn’t understand all the difficult words. But it never occurred to me that, one day, I would ignore Tezuka to make Jungle Taitei” [71].

Jungle’s production was highly hierarchical and nothing was left to chance. Under Yamamoto, work was divided into clearly-defined sections, each of which had its own director (kantoku). The 7 episode directors were initially led by Yamamoto himself as chief director, then by Rintarô from episode 12. The 5 scriptwriters were under Masaki Tsuji’s supervision. The positions of art and photography director were created, respectively handled by Tsuyoshi Matsumoto and Tatsumasa Shimizu. Chikao Katsui became Mushi’s first series animation director. Atsumi Tashiro, a former production assistant who had created an in-house sound recording division in Mushi, was appointed sound director and would have the opportunity to play a major part in the creative process [72].

Yamamoto’s objective was essentially to rationalize animation production in terms of schedule, budget, and work, but also to improve communication at each stage of the process. First, he thoroughly changed the function of episode directors, taking away their attributions as super-animators and transforming them into technical supervisors: they regularly met with scriptwriters in order to contribute to the writing process, were made to supervise the animation on top of the animation director’s corrections (this was the birth of the enshutsu check), and had to attend the photography, editing, recording and dubbing sessions. Moreover, a system of regular meetings between the directors and the staff was established. These included not only meetings with individual animators to discuss the contents of the storyboard (the sakuga uchiawase, still part of today’s anime production pipeline), but also with representatives of each section, nominated in rotation for each episode [73]. It wouldn’t be exaggerating to say that, with this system, Yamamoto established the core structure for TV anime’s production pipeline, whose fundamental aspects have not changed since then.

Thanks to this organization and one year of preproduction, Jungle Taitei started without a hitch: the first episode was completed well in advance, in April 1965 [74]. But things didn’t go so easily until the end. I can’t pinpoint any event that caused the evident collapse of the production, but perhaps it is just the general atmosphere of the studio and the extreme pressure put by Yamamoto that precipitated some of the most tragic events in Mushi’s history. In August 1966, Yamamoto himself collapsed from overwork – but he could only afford to take one day of rest [75]. This wasn’t the worst. In March, in-betweener Yoshitaka Rachi had died at 24 from an ulcer, probably caused by overwork [76]. This must have been a traumatizing event for the entire staff, and was at least enough of a shock for the two who reported it – Yamamoto, who, as producer, must have felt responsible, and Akio Sugino, Rachi’s close friend.

Rachi seems to have been the first human life claimed by the anime industry, but he wasn’t the last one. In a later interview, Akihiro Kanayama said that he couldn’t even remember how many people died during his time in Mushi [77]. Yamamoto tells the story of animator Motoaki Ishii, who started drinking compulsively because his hands trembled so much that he couldn’t draw while sober, and who later died in a car accident – the accidental nature of which Yamamoto can’t help but question [78]. As always with Yamamoto, things maybe didn’t happen in this exact order to this exact person. But the sequence of events, at least, is believable: Mitsuo Shindô, in-betweener on Atom and key animator on Jungle, said that people in Mushi became “neurotic” and personally developed an eating disorder, gaining 15 kilograms during his first year in the studio [79]. Jungle Taitei wasn’t even Mushi’s worst production, a title that probably goes to 1001 Nights or Ashita no Joe. But its cost was still unbearable.

Mushi’s masterpiece

No work of art can justify claiming human lives. It would be wrong to frame lost and broken lives as a sort of “sacrifice”, however vain, that Mushi had to pay. On the other hand, it would be mistaken not to see Jungle Taitei for what it is: one of the studio’s greatest achievements and a turning point in anime history. It was the studio’s most costly production yet and drained up most of its human resources. The narrative limitations imposed by NBC were used as an advantage, as the generation of animators and directors trained on Atom exploited them to turn the show into what is probably the first true “experimental” TV anime. Made outside of Tezuka’s control and incurring his discontent, it did illustrate that “art” and “entertainment” were not contradictory, thereby laying the ground for the core principles that would drive the future work of some of Jungle’s team, such as Yamamoto, Rintarô, Toshio Hirata or Masami Mori.

The first challenge they faced was how to depict Africa. No one in Mushi had ever gone there, and location hunting on the spot was unthinkable. Whatever reference material Yamamoto and producer Yoshihiro Nozaki tried to dig up was unusable, as photography books were all in black-and-white [80]. Moreover, NBC’s demands and the necessary break away from the manga’s narrative meant that any attempt at a realistic depiction of life in Africa – whether native populations or colonial residents and Western tourists – was out of the question. In agreement with the rest of the team, Yamamoto therefore decided to ditch realism altogether and turned towards an expressionistic, modern style built on solid colors and a sense of texture.

The colors of Jungle Taitei

The result, graphic designer Tsuyoshi Matsumoto’s art direction, is still unparalleled. The background art is one of the most appealing aspects of Jungle Taitei: its world is vibrant, varied and never boring. It probably served as a major inspiration for episode directors, who would showcase it in long, meditative pans or go further in the way of expressionism.

Jungle’s second major appeal was its music. The composer was Isao Tomita, who had by this point worked on multiple live-action drama series for NHK and had apparently been recommended by sound director Atsumi Tashiro [81]. Writing his music once the rush film had been completed, he strove to match the timing of the animation to the rhythm of the music and always discussed the contents of each episode with their directors. This was perhaps not the most time or cost-saving way to go (it’s said that most of Jungle’s budget actually went to the music), but it allowed the sound and images to perfectly match each other. This collaborative process also enabled Jungle to turn into an anime where music would play a major part: on episode 1, Tomita suggested using an insert song during the final scene, the lyrics of which were written by Yamamoto; then, later on in the production, the show turned into a musical proper. This changed the workflow quite a bit as, according to Masaki Tsuji, music now came first: Tomita composed the music, animation (or just the storyboard?) was produced, and the scripts were written last [82]. With the arrival of jazz performers such as Minoru Muraoka, Jungle Taitei’s modernism and experimental dimension just kept going further. But they didn’t go against the show’s commercial nature, as Jungle Taitei was the first anime to sell its own records – an idea apparently suggested by Kaoru Anami [83].

All these elements coincided in the show’s spectacular opening. Lasting no less than 2 minutes, it was directed by Yamamoto and Rintarô, animated by Chikao Katsui, photographed by Tatsumasa Shimizu and set on a track by Tomita. It opens on two extremely long – 23 and 27 seconds, respectively – and intricate shots, continuous pans in which background layers never stop moving and extremely complex animation – a 180° rotation and a flock of flamingos – follow each other. Photography is not limited to multiplane shots, but also to two instances of backlighting to represent the sun, the second of which perfectly matches the final fade to black. The instrumental and chorus music which accompanies these impressive visuals gives the whole a majestic atmosphere and makes this opening one of the most impressive pieces of animation from 1960s Japan.

The show itself somewhat betrays this “majestic” dimension. The main conceit of most of the story – carnivores trying to live without eating meat – is itself strange, but only becomes weirder because of the total absence of narrative structure or continuity, a direct result of NBC’s demands as well as the strange workflow adopted in the second half. The first few episodes in particular make little to no sense, as the manga’s storylines are rushed and the narration seemingly arbitrarily switches from flashbacks to current events and makes ellipsis on ellipsis. The complete absence of realism is a success in all aspects but the writing, in which the suspension of disbelief is often pushed to its limits: it seems that the viewer, even if they’re a child, is not taken seriously at all. But when it works, it does produce some very fun, if outlandish, stories.

This is not to say that the production system set up by Yamamoto didn’t work, because it certainly did. The best example would be the collective works that are episode 1 and the two parter made up of episodes 34-35 – episode 1 only made by Rintarô, Nagashima and Chikao while episodes 34 and 35 are in the hands of the entire directors’ team. Collective storyboards were unprecedented and seem to have made things more difficult for scriptwriters, who had to make do with the demands of not just one, but multiple directors at once [84]. Perhaps this played in the strange pacing of the early episodes. But this also allowed for considerable stylistic diversity. On episode 1, it seems that Chikao storyboarded (and maybe also animated?) all of the A part, since Masaki Tsuji claims that the first half of the B part, until Leo’s escape from the boat, was by Nagashima, and Rintarô says he did at least the last 5 minutes of the episode [85]. About this final scene, Rintarô told an anecdote which perfectly illustrates the close collaboration between sections – in this case, direction, art and photography, to which we should add sound since it is on this scene that the insert song composed by Tomita and written by Yamamoto is played.

“I wanted to show the sea at sunset from a bird’s eye angle, but I didn’t want the glimmer to be done with animation as we’d usually do. I talked about it to Shinji Itô from the art department, and what he did was to trace colored lines (orange, blue, etc.) on one long cel. He did that with another cel, and during the photography, we put those two above the background and slowly moved them. On top of that were Leo swimming and the white track he leaves behind.”

This scene from episode 1 is a very good showcase of Jungle’s artistic quality. But this overview wouldn’t be complete without the mention of at least one more episode director, who in my opinion made the best episodes in the show – Toshio Hirata. Originally an animator in Tôei, he joined Mushi sometime in early 1964 and did his first key animation on Atom, on which he claims to have learned everything about directing from Yamamoto [86]. On Jungle, he initially began as an animator, but was promoted to direction on episode 23, which showcases the key aspect of all his episodes on the show: a focus on horror/fantasy narratives. Thanks to this, they are also some of the most dramatic episodes. The opening scene, a wonderfully atmospheric musical number relying on complex multiplane photography and the use of colors, is a perfect example.

Hirata’s episodes are perhaps the most visually rich and experimental of Jungle Taitei. Just like Rintarô, he seems to have worked in close collaboration with the background and photography teams so that his episodes would be complete spectacles not just relying on the (sometimes excellent) animation. The result was a clear visual-centrism, but not one in which visuals only exist for their own sake: in fact, all of Jungle Taitei exhibits a mastery of cinematic and animated visual vocabulary as such, but also to convey actual dramatic intents through visual symbolism. In other words, episodes had a distinct voice behind them, which they didn’t have on Tetsuwan Atom, despite their undeniable creativity, until the arrival of directors like Yoshiyuki Tomino and Osamu Dezaki at precisely the same time. The rationalized, communication-centered production system established by Eiichi Yamamoto succeeded in at least one dimension: it not only produced obvious artistic quality, but also the emergence of animation artists as such – or, in other words, what one may call anime’s first auteurs.

With the huge number of new employees in Mushi between 1964 and 1966, Jungle Taitei wasn’t just a platform for ambitious young directors: it was where many of Mushi’s future best animators made some of their first work. The three most important, who all did in-betweens on the show and were sometimes promoted to key animation, were Akio Sugino, Shingo Araki and Akihiro Kanayama. What is striking about this trio is not just that they entered Mushi at roughly the same time, and that they would all work together on Ashita no Joe a few years later: it is that they had remarkably similar profiles, seemingly shared by many other Mushi animators. Born between 1938 and 1949, they had all read Tezuka’s first successes as they came out – either Shin Takarajima or Tetsuwan Atom. By the mid-50s, they became avid gekiga readers and contributed to the movement by writing their own gekiga works, all three submitting them to the same magazine, Machi – also where Osamu Dezaki published his work. Then, after spending some years as manga artists, they entered Mushi and started out as animators.

In any case, Jungle Taitei’s qualities were not appreciated equally. The show won multiple awards for its artistic quality and music, but it seems that many fans of the manga didn’t appreciate the changes, sending angry letters to Tezuka who in turn complained to Yamamoto [87]. Moreover, ratings were never very high, falling as low as 17% by Summer 1966 – which was not an encouraging number back then [88]. As a result, Yamamoto lost the complete control he had over the series: its continuation, Susume Leo, kept the same staff, but it would now be under Tezuka’s supervision [89]. I haven’t been able to watch any of Susume Leo’s episodes, so I can’t tell whether Tezuka’s arrival put an end to the experimental streak, or whether it disorganized schedules to the point of affecting the quality of episodes. But in any case, the mangaka’s contributions didn’t help the show’s popularity: it was discontinued after only 26 episodes.

Conclusion: on legacies and lack thereof

It could be said that, between late 1964 and late 1966, Mushi Production was dominated by its producers – Kaoru Anami and Eiichi Yamamoto. Acknowledging the new conditions they had themselves created with Tetsuwan Atom, they proceeded to create a new production model in order to generate profit, lower costs, and make production more efficient. Their efforts directly caused frictions and dramatic incidents, but it can be said that, in the short term, they largely succeeded: Mushi’s debt was soon cleared out and the studio became a merchandising and publishing powerhouse; animation production managed to remain on budget and schedule while providing major creative opportunities for those involved in it. But what about the long term? What were the wider-ranging effects of the system both men established?

Let’s start with Yamamoto and Jungle Taitei. Its production system was both incredibly rigid (because of its well-defined hierarchy) and fluid (thanks to the constant contact between divisions) and seems to have had direct effects on Mushi Pro’s other works: on Atom‘s last phase, but also on their followers Goku no Daibôken and Ribbon no Kishi, both of whom Yamamoto claims were “producer-led” projects [90]. Yamamoto built what Mushi’s employees called a “producer system”, which ensured that most of the show’s productions until the last years would remain on schedule and budget.

Outside of Mushi, the immediate thing that comes to mind when thinking about Jungle’s legacy would, of course, be studio Madhouse: the number of people in common, the spectacular approach to direction – including a focus on images and visual symbolism, but also sound design and music – and the rejection of the distinction between “arthouse” and “entertainment” seem directly connected. It may indeed be possible to tell that Jungle was a foundational experience for all those who worked on it, but that is not all: even Madhouse’s opposite, Studio Sunrise, was created by ex-producers with the intent of reviving and keeping the producer system, which had by that point collapsed in Mushi.

Moreover, as I hypothesized above, I believe that it is at least partly on Jungle Taitei that some of the distinctive elements of anime’s production pipeline were put to the test, such as the technical specialization of the episode director and the constant communication through repeated meetings. This remains very hypothetical, as the specific evolution of Mushi’s pipeline(s) and a thorough comparison between studios through time would be necessary to show whether or not Jungle Taitei’s organization had any real effects. But even if it didn’t, I do believe the show can be held up as a sign of the prodigious maturity of 60s anime not only in terms of aesthetics, but also of work division.

Now, what about Anami and his own innovations? While the basic structure of the “Anami system” remained in place until Mushi Trading’s collapse in 1973, the system only worked in earnest for 3 months, between September and December 1966, before entering a slow but inevitable decline and losing all substance by 1969. The reason for it is simple: the man who held it together and defined its purpose disappeared unpredictably and suddenly.

On December 19th, 1966, Kaoru Anami collapsed in the studio. He died the next day at 42, without seeing the last episode of Tetsuwan Atom [91]. The cause was an aneurysm – nobody could have seen it coming. This was a disastrous event, the importance of which must not be underestimated. Anami was the one who had made Tetsuwan Atom possible, Mushi the most important animation studio in Japan, and laid the ground for what might have become a media empire centered on Tezuka’s IPs. With his death, his ambitions vanished to nothing – the new studio and theme park projects were immediately canceled [92].

But he was also the one who ultimately caused the downfall of everything he had built. In his papers was found a contract stating that Mushi acquired a debt of almost 140 million yen to Fuji TV and ceded all of its film assets to the TV station. It was signed with Tezuka’s personal seal, which the mangaka had ceded to the managing director to use freely: it was therefore perfectly valid and Tezuka failed to renegotiate the contract with Fuji. After Anami himself had cleared the studio’s debt, this single document set it for good on a vicious cycle of indebtment, of which it would never get out and ultimately led to its bankruptcy in 1973. Anami left nothing explaining the reason for this contract – probably to pay for the new studio and theme park project – or how he planned to repay the debt [93]. This was the beginning of a long, slow and painful decline for Mushi.

Notes

[1] Itô,& Nagao 2001, vol.4, p.2

[2] Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.5, p.8

[3] Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.6, p.6

[4] Tezuka 1996, vol. 2, p.60. Kanayama 2000, p.3 claims Mushi had 700 employees at its peak. Some other accounts also go as high as 600. However, Tezuka’s text is chronologically much closer to the events (1973) and, given its context (Tezuka lamenting how Mushi Pro becoming a factory-like entity completely different from what he envisioned), I don’t think the mangaka would have deflated the numbers

[5] Udagawa 2005, p.274 & Takahashi 2019, p.10

[6] Takarajima Editors’ Room 2018, pp.98 & 135; Sugii 2015, p.92

[7] Kanayama 2006; Takarajima Editors’ Room 2018, p.76; Kawajiri 2008, p.35. Kanayama’s brother worked in Tôei, and introduced him to Daisaku Shirakawa, who in turn introduced him to Tezuka and had him enter without passing the exam. As for Kawajiri, he lived near the house of animator Hideaki Kitano’s mother, who introduced him to her son, who made Kawajiri enter Mushi

[8] Udagawa 2005, p.274; Takarajima Editors’ Room 2018, p.98

[9] Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.5, p.8; Nakagawa 2020, p.259

[10] Toyota 2020, p.86

[11] Shimotsuki 2011, p.131

[12] Cited in Chûjô 2015a, p.9

[13] Shimotsuki 2011, p.88; Takarajima Editors’ Room 2018, p.118

[14] For more on the connections between Hols and Sanpei’s work, see this article

[15] Shimotsuki 2011, p.117

[16] Shimotsuki 2011, p.141

[17] Chûjô 2015 p.8; Shimotsuki 2011, p.122

[18] Shimotsuki 2011, p.122; Holmberg 2011a

[19] Shimotsuki 2011, p.142

[20] Shimotsuki 2011, p.148

[21] Shimotsuki 2011, p.148

[22] Shimotsuki 2011, p.151

[23] Shimotsuki 2011, p.151-152; Holmberg 2011a

[24] Yamamoto 1989, pp.211-212; Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.6, p.6; Nakagawa 2020, p.260.

[25] Yamamoto 1989, pp.211-212; Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.6, p.6; Nakagawa 2020, p.260

[26] Nakagawa 2020, p.260. Nakagawa claims that Mushi Trading paid off the debt “extremely quickly”, but gives no more details. On the other hand, the Japanese Wikipedia page of Mushi Pro says that a debt of the same amount was completely paid off in May 1969, though the lack of detail makes it hard to know if it was the same debt or how it was repaid. It’s also possible that Nakagawa confused the numbers and attributes to 1965 Mushi a much higher debt than it actually had

[27] Shimotsuki 2011, p.147; Makimura and Yamada 2015, p.20

[28] Nakagawa 2020, p.260; Yamamoto 1989, p.212

[29] Cited Nakagawa 2020, p.261

[30] Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.6, p.7; Nozaki 2011, p.272; Yamamoto 1989, p.213, gives a slightly different version of the story: Tezuka circulated a written survey on which was written “1) From now on, Mushi Pro’s objective should remain to create experimental works. 2) It should be to make productions to earn money”. I prefer to follow Itô & Nagao’s version, which is generally more trustworthy and taken directly from Mushi’s archives, though Yamamoto at least confirms that this indeed happened. Furthermore, Nakagawa claims that this only happened much later, in 1971, and that the results led to Tezuka’s departure. It’s possible that Tezuka tried the experience one more time, but I find it unlikely – Nakagawa may have confused the dates for some reason

[31] Yamamoto 1989, p.213

[32] Cf. Mushi Production 1977, p.7: Pictures at an Exhibition at least was made with Tezuka’s own money. Moreover, Tomioka 2015, p.242 mentions that whatever manga-related activities Tezuka organized were to be paid with his personal funds

[33] Nakagawa 2020, pp.261-262

[34] Nakagawa 2020, p.179

[35] Nakagawa 2020, p.192; Tezuka 1999, p.664; Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.3, p.9

[36] Yamamoto 1989, pp.123-124

[37] Tezuka 1999, p.664; Kurosawa 2010c; Nakagawa 2020, p.193

[38] Nikaidô 2006, pp.75-76; Toyota 2000, p.155-156. Yamamoto 1989, p.162 also discusses Sakamoto’s departure, but in incredibly vague terms, only saying that “reality failed to meet his expectations”. I read this as meaning that Sakamoto dropped out of frustration rather than because of a conflict with Tezuka – which appears slightly more credible to me, as Tezuka doesn’t seem to have been the kind of person who would have driven one of his close colleagues to leave a common project

[39] Nakagawa 2020, p.195

[40] Nakagawa 2020, p.195; Toyota 2020, pp.97-98. In Tezuka 1999, p.664, animator Junji Kobayashi claims that “no culprit was found”, but this was probably written to avoid hurting anyone’s reputation at a time when the case was not that well-known and Toyota was still very active. I’ve also seen it claimed that Sakamoto was suspected and that this led to his departure, but this is certainly false. Not only is this not substantiated by any of the sources I consulted on the issue, it fails to explain why Sakamoto kept working in Mushi until at least late 1966 and seems to mistake the date of his dropping from Number 7

[41] Toyota 2000, p.161

[42] Toyota 2000, p.162, 2014 p.228 & 2020, p.98. For those curious and a bit aware of how Japanese works, Toyota mentions this was the only time he ever saw Tezuka drop the polite desu/masu forms.

[43] Toyota 2000, p.157

[44] Nikaidô 2006, p.76. According to Kurosawa 2010, Tezuka claimed that it was Kodansha’s editors who discontinued the manga, but the magazine’s editor, Teruo Miyahama, attested to the contrary. Given Tezuka’s apparent distress at the time, I think Miyahama’s version is the most credible

[45] Sugii 2015, p.167; Nakagawa 2020, p.196

[46] Tomioka 2015, p.242; Cinema Novecento 2020, p.48

[44] Nakagawa 2020, pp.208-209

[45] Nakagawa 2020, p.263

[46] Yamamoto 1989, p.170; Tezuka 1999, p.664; Nakagawa 2020, p.211

[47] Nakagawa 2020, p.211

[48] Sugiyama 2010, p.318

[49] Yamamoto 1989, p.170

[50] Takahashi 2019, p.12; Masami https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mcsammy/e/a7bbeed3bdd5308a0881e78abb57d893

[51] Masami https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mcsammy/c/7c18f91709c190eda47c6f78457fd7c6

[52] Masami https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mcsammy/e/6a3e759e276aafec9f555203a764b1b2

[53] Nakamura 2007, p.284

[54] Tezuka 1999, p.664; Sugii 2015, p.180. I couldn’t find where Otsuka told the story (at least, it’s not in Drawings Drenched With Sweat), but Sugii’s version is a bit different from the one that’s usually told: Sugii says that he was in Nakamura’s car alongside Otsuka, and that he was the one to call Otsuka (not Anami) to ask him to work on the W3 OP, seemingly without any relation to the crash

[55] Otsuka 2001, p.98; Sugii 2015, p.180 & p.203 for Fujimaru

[56] Sugii 2015, p.177-178

[57] Tezuka 1999, p.664

[58] Nakamura 2007, p.285, Kurokawa 2018, p.292

[59] Yamamoto 1989, p.106

[60] Sugiyama 2010, p.318

[61] Takahashi 2019, p.11; Kurokawa 2018, p.291

[62] Nakagawa 2020, p.180

[63] Nakagawa 2020, p.179

[64] Yamamoto 1989, p.156; Tsugata 2007, p.129; Nakagawa 2020, p.180. In Yamamoto et al. 2004b, Yamamoto gives 2.8 million, which is further corroborated by Nozaki 2011, p.272

[65] Yamamoto 1989, pp.153-154; Tsuji 2006

[66] Yamamoto 1989, p.154; Sensô 2019, n°3

[67] Nozaki 2011, p.273

[68] Yamamoto 1989, p.158; Nakagawa 2020, p.181

[69] Yamamoto 1989, pp.169-170; Itô & Nagao 2001, vol.4, p.2; Nakagawa 2020, pp.205-206

[70] Masami https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mcsammy/e/8972b72af09911140ad4a5773fe8d614

[71] Yamamoto 1989, p.171; Masami https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mcsammy/e/a16b5d6927e17f9f79f8808215945917

[72] Sugii 2015, p.211; Cinema Novecento 2020, p.134

[73] Yamamoto 1989, p.200. With the only source on this overhaul of the pipeline being Yamamoto himself, caution is in order, as he may have exaggerated the degree of rationalization and efficiency of the production. However, while they don’t go into the details of the changes, both Yoshihiro Nozaki (2011, p.272) and Atsushi Tomioka (2015, p.241) credit Yamamoto for “fixing up” Mushi’s production system. Similarly, Jun Masami details Yamamoto’s changes on the financial side at least. The assignment of “directors” to each part of the process, at least, is attested by credits. However, Jungle Taitei’s credits do not really match the current terminology, as none of the people cited here is credited under “… kantoku”. Katsui, for example, is only credited under sakuga. Having Jungle Taitei‘s organization chart available would of course make it possible to examine things in more detail. As a side note, it may be possible that the Atom organization chart I discussed previously was inspired by Jungle‘s, meaning that Yamamoto’s system had direct effects in the entire studio

[74] Masami https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mcsammy/e/f030c07776092b72fbc2eaa6d51af07b

[75] Yamamoto 1989, p.210

[76] Yamamoto 1989, p.210; Takarajima Editors Room 2018, p.121

[77] Kanayama 2006

[78] Yamamoto 1989, pp.160-161

[79] Shindô 2005, p.286

[80] Yamamoto 1989, p.159; Nozaki 2011, p.272

[81] Yamamoto 1989, p.173; Cinema Novecento 2020, p.25

[82] Mushi Production 1977, p.27; Yamamoto 1989, p.174; Rintarô 2009, p.44; Cinema Novecento 2020, p.135; Masami https://blog.goo.ne.jp/mcsammy/e/dbef0610354b32d1b0301c1384666953. Rintarô claims he was the one to suggest turning Jungle into a musical, while Tsuji says that it was Tomita and him

[83] Yamamoto 1989, p.207; Nakagawa 2020, p.263

[84] Tsuji 2006

[85] Tsuji 2006; Rintarô 2009, p.39

[86] In Rintarô 2009, p.152; Hirata 2007

[87] Yamamoto 1989, pp.202-203

[88] Nakagawa 2020, p.264

[89] Nakagawa 2020, p.264

[90] Yamamoto 1989, p.211

[91] Yamamoto 1989, p.222; Tomioka 2015, p.244; Nakagawa 2020, p.269-270

[92] Yamamoto 1989, p.222

[93] Nakagawa 2020, p.272

This history is absolutely crammed with info that seems to contextualize everything. The only story I really knew from this was the W3 controversy and pretty much everything else was brand new.

I love the specific production dates for a real sense of how hard artists had to work to get these things done. I love the side story of how the doujinshi scene evolved out of their fan magazine into Comiket. I love that ominous ending. You’ve produced an incredibly thorough picture of Mushi Pro’s impact on animation in this post in particular.

It’s a shame that the Disney animators will never be able to acknowledge Jungle Tatei’s impact on The Lion King, which becomes clearer the more I see of the former. Its artistry is destined to remain relatively obscure in the West, mainly seen only through that hidden connection. Even beyond the strict “sakuga” cuts I love how that show deals with the animation of its more grounded characters. It’s really beautiful stuff, almost unmatched in 60s and 70s TV animation from a design standpoint.

Keep up the stellar work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for your comment! I’m so glad to know you’ve enjoyed this piece.

To be honest, I’d rather not discuss the Lion King thing, as I have absolutely no interest in it and believe that subject to be rather sterile (a bit like the Aaronofsky/Kon plagiarism thing). But yes, I’d really love more people to be aware of Jungle Taitei at least, it really deserves it.

LikeLike

Very much enjoying this deep dive into Mushi Pro. Possibly I have missed a previous instalment that explains your reasoning, but you have a location listed as “Lalamy Ranch”; surely this is supposed to be Laramie Ranch, named for the TV show Laramie that ran in the US from 1959-63, and in Japan from 1960-63, where it was released as ララミー牧場.

I see you mention earlier on that it was based “on a popular drama which ran on NHK at the time” but I suspect that is a hazy misremembrance from one of your sources, as Laramie actually ran on NET Terebi (i.e. the channel that would become TV Asahi).

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%83%A9%E3%83%A9%E3%83%9F%E3%83%BC%E7%89%A7%E5%A0%B4

LikeLike

You’ve got it right!

Also thank you for actually checking, which I didn’t bother doing!

LikeLike