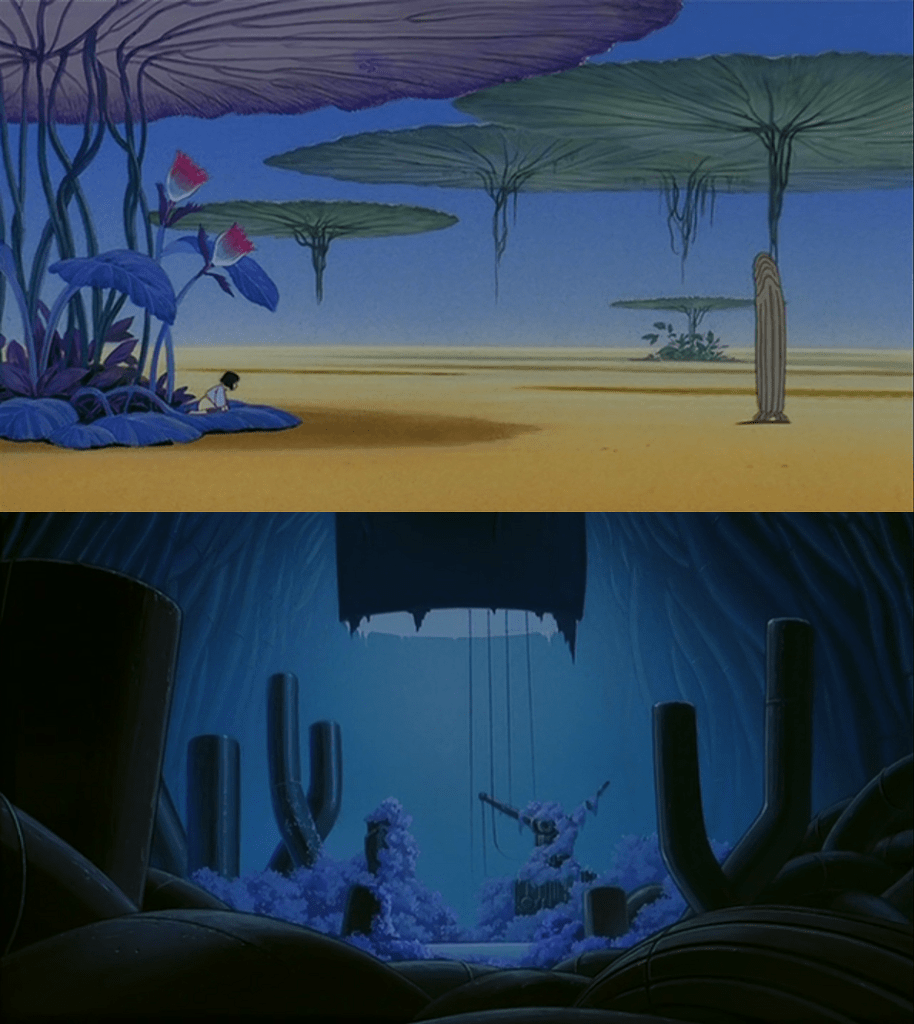

Cover image: a layout from A Tree of Palme by Takashi Nakamura (?)

This article is part of the History of the Kanada school series

Yoshinori Kanada might be the most influential Japanese animator, but he isn’t the only one whose work revolutionized anime. Almost as important as him is Takashi Nakamura. Nakamura is very interesting, because he could be considered like an anti-Kanada, even though he also got influence from him. In an earlier post, I described Kanada as the quintessential Japanese animator, because he made a synthesis between the two divergent aesthetics of anime in the 70’s. On the other hand, Nakamura’s inspirations are far more diverse, and he owes a much larger debt to Disney and Western animation. Moreover, whereas Kanada can be said to have brought out the full potential of limited TV animation by modulating and lowering the framerates, Nakamura did the exact opposite. He pushed the limits of what could be done with TV animation by raising the framerates and aiming for realism and detail above all else. But his work as an animator has been somewhat forgotten by Western animation fans, so it’s time to do him justice.

Nakamura’s profile was initially very similar to that of another young talent I covered earlier, Kazuhiro Ochi. He was born in 1955, in the mountainous Yamanashi prefecture. At 16, aiming to become a mangaka, he moved to Tokyo and entered studio Tatsunoko, first as a colorist and then as an in-betweener on Science Ninja Team Gatchaman, in 1974.

Being a Tatsunoko alumnus is the first thing that makes Nakamura original. Back then, the studio was something of an industry within the industry, with its own special aesthetic and animation philosophy. Thanks to the work of character designers Ippei Kuri and Yoshitaka Amano, their productions looked wildly different from the rest of anime and were heavily influenced by American comics and cartoons. At the time, the studio’s foremost animator was Masami Suda. Although a freelancer, he was Tatsunoko’s ace and Nakamura’s direct teacher. Besides Suda, Nakamura might also have met a future legend of character design and animation, Tomonori Kogawa, another freelancer working for Tatsunoko who would create the legendary studio Beebow.

However, Nakamura’s most important encounter in those early years was with animator Hirokazu Ishino. Ishino was a member of Anidô, an association established by figures from all over the industry (among them Hayao Miyazaki and Isao Takahata) in 1967. Anidô’s goal was (and still is) to be a place for animators to meet, exchange and train, and in that effect it organized many screenings of animated movies from all around the world. These screenings were a central meeting place for all industry members, especially the young ones: it’s reportedly in one of those that Yoshinori Kanada and Kazuhide Tomonaga first met, for instance. There, at 18, Nakamura discovered that the world of animation went far beyond TV anime: he got acquainted with the works of Norman McLaren and Alexander Alexeïev, but also pioneer indie Japanese animators like Kenzô Masaoka and Noburo Ofuji. The two most important works he watched were, however, Takahata’s Hols, Prince of the Sun and Disney’s Fantasia. What seems to have impressed him the most was the effects animation in both movies, and he has stated that his own unique debris animation was directly influenced by Yasuo Otsuka’s work in Hols.

The Anidô screenings determined Nakamura to quit making manga on the side (although he would fall back into it in the mid-80’s) to pursue a real career in animation; while still a frequent audience member of Anidô, he left Tatsunoko in 1976 for a small outsourcing studio called Wako Pro. It’s there that he made his debut as key animator on Blocker Gundan IV Machine Blaster, an Ashi Pro/Nippon Animation super robot series. He jumped from one little studio to another (from Waki Pro to Anime Room and then Green Box) before going freelance, and his responsibilities slowly increased at the time: he was animation director on some episodes of Yatterman in 1978, and did his first character designs for episode 8 of Manga Nihon Emaki.

It’s in 1979, while he was still in Anime Room, that Nakamura discovered Kanada’s work on Galaxy Express 999. He was already starting to specialize in mecha and effects animation, but Kanada’s apocalyptic finale must have convinced him to go even further in that direction. The two men quickly had the opportunity to meet each other, as Nakamura was assistant animation director on Be Forever Yamato, directly under Kanada who was joint animation director. It was just a year after that, in 1981, that Nakamura made his real breakthrough on the Tatsunoko series Gold Lightan. He was animation director and key animator on 7 episodes, with three (22, 30, 41) entirely solo.

There’s still a lot of Kanada in Nakamura’s work at this point, especially in the fire, smoke and water effects, as well as in the character animation. But what already set him apart was his approach to timing: he was animating mostly on 1s and 2s, on a TV production. Nakamura was given less than 2 months for his episodes, and being able to put out such detailed and fluid work on such a tight schedule was a testament to his demanding nature and talent. This came out even more clearly on his fighting scenes, where his sensibility for debris animation freely expressed itself.

In this sequence, Otsuka’s influence is really visible, especially in the irregular geometrical shape of the debris. But what’s so striking is the diversity of their shapes (each one is unique, so Nakamura wouldn’t just recycle the same cels), their number, and their motion. Nakamura used all the possibilities of framerate modulation to animate these bits of rock: they oscillate freely between 1s, 2s, 3s and sometimes 4s. Their movement seems almost surreal. Just like Kanada had revolutionized mechanical animation by animating machines like people, Nakamura did with debris: with their irregular framerates and free motion across the screen, all the flying objects look like they have a will of their own. They would quickly go on to be nicknamed “Nakamura debris” and influence the dense effects animation you find later in the 80’s in the work of people like Masami Obari or Hiroyuki Okiura.

A notable element about Nakamura’s career is that it went quite fast, even for someone who entered the industry so young. After Lightan, 1983 and 1984 were blessed years, during which he would cement his role as one of the most important animators in the industry. He was key animator on Genma Taisen, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind and Macross: Do You Remember Love, as well as joint character designer for Mirai Keisatsu Urashiman and animation director on multiple episodes of the TV series. Nakamura had already pushed the limits of what it was possible to do in TV with his Gold Lightan work, and he was now ready for movie production.

Genma Taisen was a monumental movie which set the groundwork for most of what was to come in the realist school. Maybe more than any other Rintarô work, it was very much an animator’s movie. As Nakamura tells it, he was able to freely chose his cuts in the storyboard that Rintarô had presented to him. He decided to animate the Shinjuku scene and part of the New York one. On the movie, he met his first student, Kôji Morimoto, who had decided to enter the industry after watching Osamu Dezaki’s Gamba no Bôken and Nakamura’s Gold Lightan episodes. They would keep working together on Urashiman and many shorts and OVAs.

To be honest, I’m torn about some of Nakamura’s character animation on Genma Taisen – it was not (yet) his strongest suit, and you feel it in some of his sequences. This is for example the case on this one. Joe’s motion in the first shot is very irregular, and the animation brutally jumps from 1s to 5s without any in-betweens. This is so stark it has to be intentional, but it ends up feeling more awkward than anything. However, in what follows, the animation of all the objects in the room taking life is exemplar, with the strange shapes and strong shadings taken by fabrics, or the complex trajectory of each object. Although they’re all in cycle, it must have remained an incredibly complex work to plan out and animate. Nakamura was probably the only one able to handle such a moment.

His next major work was on Nausicaä. Like many animators on the movie (including Kanada), he was initially intimidated to work with Miyazaki, especially since the latter had a very different animation philosophy than Rintarô. But that didn’t stop Nakamura from delivering some impressive work. His flying scenes were easily at the same level as Kanada’s, with a lot of attention put into the volume and movement of the airships, and in the texture of the clouds.

But Nakamura’s standout sequence was without any doubt the opening scene of the movie, in which a wild Ohmu goes on a rampage. Again, the smoke effects are very well handled, with a kind of dense volume that was still very rare at the time. In terms of debris, his characteristic triangular shapes are everywhere and brought a real impact to every little explosion. But what’s really impressive here is Nakamura’s flawless mastery of space, especially starting 0:23. Nausicaä runs and flies away and towards the camera and her glider rotates with amazing ease. For the first (but not last) time in Nakamura’s career, background animation is prominent and contributes to creating exhilarating movement. The layouts are incredibly complex, and yet very simple – there aren’t many elements in the frame, but the motion is elaborate.

It is in the last four shots of this sequence, however, that Nakamura went wild. As the monstrous Ohmu suddenly emerges out of the forest, the trees explode in all directions. This moment is on 2s, with the Ohmu moving on one frame and the debris on the other. Like in all of Nakamura’s cuts, the density is impressive – the fact that he managed to handle so much movement on a single cel makes this jaw dropping. And yet, it is still perfectly readable, thanks to Nausicaä’s more gentle lateral movement on her glider.

I mentioned background animation, but it was on Do You Remember Love that Nakamura exhibited his total mastery of this technique. This sequence was a symbolic one: in the Macross TV series, the corresponding moment was one of Ichirô Itano’s most impressive works. It was, in a way, Nakamura’s confrontation with the other most prominent effects and debris animator of his generation. And he pulled it off superbly. In the first part of the scene, as all objects in zero gravity start flying around, everything looks like it’s going in slow motion, giving it all a surreal, dreamlike atmosphere.

But we’re brought to reality with Minmay’s fall and Hikaru going to save her. The moment when he notices her from his cockpit and starts his machine is already exemplary – a very short but very precisely animated rotation. Then, in the sequence that goes from 0:25 to 0:32, what’s impressive isn’t so much the background animation in itself (although it is very well handled) but the camera movement. The Valkyrie first approaches Minmay in a zig-zagging trajectory, but just as it’s about to reach her, the camera moves slightly upwards, helping the viewer to appreciate the distance but also forcing the animator to rework all the proportions. And then the camera moves back down, again changing the proportions and angle of the mecha, but allowing us to see Minmay’s face and her ongoing fall past the camera. Finally, from 0:38 to 0:45, it’s time for beautiful mechanical animation, which shows how delicate the operation is and how gentle the Valkyrie’s movement is.

I’ve covered Nakamura’s following work elsewhere, but needless to say that the years 1985-1988 were decisive in his career. Still as a freelancer, he worked a lot with Madhouse along with his protégé Kôji Morimoto, and closely followed Katsuhiro Otomo. With all he had done on Genma Taisen and Nausicaä, he had by then completely mastered character animation, giving it a yet unprecedented (except maybe for Tomonori Kogawa and Yoshikazu Yasuhiko’s work) sense of weight and grounding. It was after that, in 1988, that Nakamura’s crowning achievement came out: Akira. Although he had already taken the role on TV episodes and shorts, this was his first work as an animation director on a full-length movie. As much as I emphasized Nakamura’s role as a teacher to the staff of Akira in the article about realism, it must also have been quite the learning experience for Nakamura as well.

With as many talents as Toshiyuki Inoue, Satoru Utsunomiya, Yoshiji Kigami, Kôji Morimoto and all the others, it’s hard to estimate precisely how much work Nakamura delivered on the movie and how heavy his corrections were. But it certainly was a turning point. In terms of what he could do as an animator, he described it as “having reached his limit”. His relationship with Otomo must have been quite close, and he probably had to take a lot of decisions by himself; but the director was famously exerting a lot of control over the production, and maybe Nakamura felt stifled. He had also had his first taste at directing on his Robot Carnival short. Therefore, he would slowly quit being an animator for others than himself and start working on his own projects.

His first work just after Akira was on 1989’s Peter Pan’s Adventure, as character designer. This show was a strange entry in the then already venerable World Masterpiece Theater series. It was getting old, and Nippon Animation wanted to revive it by shaking things up. Therefore, they decided to adapt a story far more famous than everything they had previously done, and gave the direction to their veteran director Yoshio Kuroda and the character designs to Nakamura.

For such a Disney fan as him, this must have been something of a challenge – after all, Disney had already adapted the story in one of their movies. And what Nakamura decided to do was to go in a radically opposite direction – in contrast to the flashy colors and sharp shapes of the Disney designs, his characters were round and simple, bland in a good sort of way. They didn’t stand out but were expressive and, more than anything, easy to animate. These traits would stay characteristic of Nakamura’s designs throughout the rest of his career.

Peter Pan’s animation is also very telling of what would follow in Nakamura’s work. He wasn’t animation director on it, probably wanting some rest after his exhausting performance on Akira. But some of the movie’s staff, more or less Nakamura’s students, were present: Hirotsugu Kawasaki, who had been an animator on Akira, was one of the most recurring animation directors on the show. Hiroyuki Okiura was also animation director on 3 of the best episodes (12, 20 and 28) and key animator on 5 others. Finally, Shin’ya Ohira was key animator on 2 episodes. Besides these illustrious names (to which I should add Mitsuo Iso), the animation is consistent, without ever being too flashy. This would become one of the key aspects of Nakamura’s works: lively and fleshed out motion that’s never there to impress you. More than any other Japanese artist, Nakamura made his the Disney principle according to which animation should aim for the illusion of life, and not movement for the sake of it.

After his standout episode on The Hakkenden, which I already mentioned elsewhere, Nakamura worked as a key animator on various movies and OVAs, most notably Junkers Come Here. But he was most probably just biding his time until 1995, when his first feature-length movie, Catnapped! came out. In its philosophy, the movie’s production seems to have been still very close to Nakamura’s shorts: it wasn’t very long (just 1h15), and Nakamura handled most creative responsibility, as director, writer, character designer and animation director. Just like for Akira, it’s hard to tell what exactly is his in the animation, because he’s everywhere.

In any case, Catnapped confirmed Nakamura’s status as one of the most original artists working in the anime industry, for two reasons. First, because he had decided to make a movie for children and for children only, much closer to Disney’s targeted audience than even that of Miyazaki’s movies (especially at the time, when 2 of his most mature movies, Porco Rosso and Princess Mononoke, had come out). And second, because his visual imagination seemingly knew no bounds and gave birth to settings of which Japanese animation had never seen the like. Catnapped’s universe is something like a large playground with its many colors and characters that turn into balloons. Even besides that, Nakamura’s obsession with dolls and the mechanical had never been more obvious than in the stop-motion opening and ending of the movie.What’s interesting is also how much Nakamura’s direction owes to Otomo’s. Or rather, how Otomo and Nakamura probably developed their styles together and explored the same things – most notably, the use of the multiplane camera. Otomo is arguably one of the unrivalled masters of the multiplane, from the daunting pull-cells of the buildings of Neo-Tokyo in Akira to the impressive Cannon Fodder, shot only with pans and fade-out transitions rather than simple cuts from a shot to another. Although less experimental and ambitious, Nakamura did similar things, with lots of pans and zooms, but also the richly detailed setting of the town in which the movie starts. It is full of layers and life just in its backgrounds.

Once again, the animation reunited many of Akira’s names and really deserves its place in the history of realist animation in Japan. There was Hiroyuki Okiura, who did no less than 40 cuts on the finale, but also Hirotsugu Kawasaki, Takaaki Yamashita, Tatsuyuki Tanaka and Toyoaki Emura. What’s also interesting is that, except for Okiura, all of them also worked on Gosenzosama Banbanzai. By 1995, the different approaches to realism had already become clear: there was the playful and liberated motion of Satoru Utsunomiya and Mitsuo Iso that had triumphed in Gosenzosama Banbanzai, the underground radicalism of Shin’ya Ohira’s “The Antique Shop” and Junkers Pilot, the toned-down and delicate, Nakamura-inspired animation of Junkers Come Here, and the heavy, photorealistic work of Toshiyuki Inoue and Okiura on Patlabor and Ghost in the Shell. Catnapped was in yet another category, which showed both that Nakamura’s students had created distinct styles while Nakamura himself kept exploring new directions on his own.

After Catnapped, his career became more diverse. His next movie, 2002’s A Tree of Palme, took him in a direction wildly different from the one explored in Catnapped: that of a complex, harrowing tale for adults, with some moments verging on horror. However, Palme was still very much a Nakamura work: a dark, metaphysical take on the tale of Pinocchio, it took strong inspiration from French artists such as cartoonist Moebius and director René Laloux. Although the movie’s writing is debated, the beautiful world explored by the characters and the amazing art direction by Mutsuo Koseki testify to Nakamura’s endless visual inspiration.

Palme was also an incredibly ambitious project that took more than 3 years to produce and ended up being more than 2 hours long. It reunited an all-star staff that made the movie one of the most visually impressive of its time: Toshiyuki Inoue reworked Nakamura’s original character designs and animated large sections of the movie, alongside other legendary animators such as Manabu Ohashi, Masahiro Ando, Shôichi Masuo, Tokuyuki Matsutake and Yasuomi Umetsu. The movie also prominently featured 3DCG animation, and masterfully so for the time, especially when you consider that it was one of the last major productions produced on cels.

Nakamura came back to TV with his character designs on the 2004 Tetsujin 28 series and directed his first show, the much darker Fantastic Children, also in 2004, that revisited many of Palme’s themes. What’s most notable, however, is that Nakamura associated with two studios at the vanguard of animation technology in the early 2010’s, Colorido and 4°C. Colorido produced his shorts, Shashinkan in 2013 and Bubu and Buburina (for the Japan Animator Expo) in 2015, while 4°C handled the more ambitious projects such as the 4-episode series Toruru’s Adventure in 2014 and the movie Harmony, co-directed with Michael Arias, in 2015. This enabled him to try out yet more new things, as Shashinkan demonstrates.

A 15-minutes silent short, Shashinkan is hauntingly beautiful and poetic. In terms of aesthetics, it demonstrates Nakamura’s definite turn, that had already begun in Catnapped, towards a picture book aesthetic. Yet again, it is quite reminiscent of Otomo’s work on Cannon Fodder. On both, the character designs are made of simple geometrical lines, but with thick borders that give them a rough, illustration-like look. They move little, but the movement they do is always fluid and expressive. But the most impressive aspects are, once again, the camerawork and the integration of 3DCG.

The particular setting – the photography studio where everything happens is up on a hill – was made just for slow panning shots and strong visual compositions, which also explained the very wide aspect ratio. In the course of the short, the photographer tries to cheer up his subjects by playing tricks or offering them objects – flowers, or a doll. These objects are in 3D, as if to show their unique nature as gifts made to highlight these unique instants. But the 3D is barely noticeable: the interaction with the 2D elements is just perfect and demonstrates the staff’s attention to detail, something that’s so characteristic of Nakamura’s work.

Takashi Nakamura’s career is very original and diverse, and definitely needs more attention. Compared to other influential artists like Yasuo Otsuka and Yoshinori Kanada, Nakamura wasn’t very prolific. But that is understandable, considering the amount of work and care he put in every one of the sequences he animated. Even then, he easily stands on the same ground as them: one of the most important Japanese animators, who revolutionized every field of animation, from effects to characters and worlds. But he never really embraced this role as a teacher like Otsuka and, to a lesser degree, Kanada did. He always remained a profoundly innovative creator, and that is part of what makes him so great.

Great write up. A few minor things I’d like to add on his work as a director:

Personally, I don’t think Nakamura’s artistic development can be traced back to Otomo. In fact, the multi-planing and panning merely resemble animetism at the time. It was such a common approach to film-making, I’d be hard-pressed to credit Otomo for it. Many other directors had already made it a staple of their toolkit prior to Otomo even entering directing. Otomo’s shorts focus pretty heavily on tracking shots (Cannon Fodder and Hi no Youjin being the most prominent offenders), something I wouldn’t even consider staple Nakamura. His most frequently used tools as a director have always struck me to be 1) extreme wide (establishing) shots from a birds-eye perspective, 2) ground-level wide shots over a flat background, 3) an above average focus on rythm (acoustic/visual interplay), similar to those whose works he likely consumed at Anidou, 4) medium close-ups allowing room to convey mannerism 5) and a combination of animetism and cinematism in how he deliberately ventured into the image while exploring multi-plane layers simultaneously.

I feel like pointing this out because if one wants to “seriously” engage with Nakamura’s work, it strikes me as a (mandatory) requirement to venture outside of Japan’s borders and cultural restraints. To find the things he drew most of his wicked ideas from one must leave that little island. For as long as I’ve bothered with this medium, I’ve considered him one of the most versatile directors in animation history and I think part of his can be traced back to how heavily his oeuvre borrows from non-Japanese sources (not to imply for his “cuts” to not appeal to me, but since I am not much of a “Sakugafan” in the western sense, his animation on Genma Taisen, Nausicaa etc. has never been something I cared about, mostly because I don’t consider many of those cuts to be “him”, but things he animated for others. The real Nakamura deliberately designs weird settings and character designs in an attempt to challenge himself in his “quest for life”, and that’s what makes him stand out, e.g. there’s something about his style of directing and the little details he adds to facial expressions manage to make his works emotionally probing, I think part of it are the implied bags under the character’s eyes).

-Chicken Man and Redneck being an obvious homage to Ichabod (in more ways than one), Fantasia (Bald Mountain) as well as Une Nuit sur le Mont Chauve (primarily because of the scarecrow, an element I am certain the Chicken Man was inspired by). I’ve always found the musical interplay to be much more reminiscent of western animation/western theatrical shorts, than the early pieces by Tezuka (e.g. Aru Machi) or those with a very strong focus on creating eerie atmosphere (e.g. Labyrinth)

-Palme no Ki not only takes from Pinocchio and Fantastic Planet on a superficial level – even feels like a response to Walt Disney’s interpretation of the source material (who himself admits to have made Pinocchio a much more likable character in hope to assure box-office success, something Nakamura’s didn’t do, Palme’s was probably made the film’s least likable character for the sake of the works underlying themes); also is similar to Fantastic Planet in many more ways than it’s aesthetic sensibilities (e.g. abuse, reaching higher cognitive state, taking up arms against superior being(s)) – but it also adds a lot of east Asian flavor by being fundamentally based religious principles sprouting from both Shinto- & Buddhism. Maybe a bit of a stretch, but I’d be anything but surprised if Nakamura also owed to numerous of Hieronymus Bosch’s works (focus on awkward subspecies, human struggle and fears, religiously inspired “layers”, Nakamura’s aesthetic sensibilities also focus on either lack of perspective or this bonbon’esque style he employed in Catnapped/Palme, afterlife and godly realm)

-rather than borrowing from Otomo’s oeuvre, Shashinkan has always struck me as an homage to Sylvain Chromet’s masterpiece Triplettes de Belleville, in how it mimics many of its elements throughout (very flat (maybe not Wolfwalkers flat, but still flat), similar color palettes, free of dialogue, littered with subdued commentary on the development of media/technology, character designs so exaggerated they act much more as motifs than mere cast members, erratic instead of artificially cleaned line-art, strong focus on sentimentalism for an art of the past)

-Nakamura’s take on character designs (scrawny, “head-heavy”, focus on joints and puppet’esque physique – particularly reminiscent of Schiele’s pre-war/pre-incarceration oeuvre) and mannerism being very clearly inspired by Egon Schiele (I considered this a complete fringe theory of mine until I – IIRC – saw Inoue specifically mention it in an interview he took alongside Imaishi); much more so than Japanese animation or even Disney, were hand movements were primarily used for no more than the goal to convey an action (Night on Bald Mountain being a good example, despite its clear focus on the demon’s hands, the hands are only used as a means for scale or to perform actions, arguably never to establish a personality), Nakamura has shown early (first examples can be found in Chicken Man and Redneck) for “hands and how they convey mannerism” to be a defining part of his craft (it’s in his work on Akira, Shashinkan, numerous segments throughout Palme, Chicken Man and Redneck)

-I don’t have the first clue what Fantastic Children took inspiration from (apart from obvious religious overlaps from Palme), but I highly doubt it were Sailormoon and Mirai Shounen Conan (despite being advertised as such). In fact, in his interview with alltheanime he not only emphasized to have an interest in “researching” old, non-Japanese animation and film, but also how much value he finds in his output being an extension of himself. Part of this can be seen in his oeuvre at large, e.g. how he adds little references of his own designs (e.g. numerous Fantastic Children’s designs are present in Catnapped, outro of Bobo to Bobulina sports Catnapped aircraft) and how Palme’s shot composition clearly took inspiration from western directors (e.g. some close-ups on SOMA are obviously Kubrick).

Despite not being in charge of correcting KA, I think he was much more involved than credits allow for us to gauge at first glance. Not only did Okiura state for Nakamura to have drawn storyboards and layouts (neither of which he is credited for), Okiura also claimed for the “special” episodes to have been the ones boarded by Nakamura. Furthermore, Peter Pan no Bouken’s OP is also way too reminiscent of Zillion’s to be a coincidence (the final 5 seconds are essentially the same). In addition, Nakamura didn’t merely serve as character- but he also served as setting designer, giving people an idea what his imagination was capable of (I’d be anything but surprised if his work on Peter no Bouken’s had been a pivotal event in his career, leading not only to Catnapped’s funding but also allowing him to explore his creativity more freely; IIRC Fantastic Children only received funding cause some capital providers really loved Palme or something, some people clearly appreciated his idiosyncrasies)

Due to it’s moral ambiguity, I wouldn’t consider Catnapped a film made for children “exclusively”. Too many heavy themes are being tackled throughout (slavery, second degree murder, (animal) abuse, hell, if one really wants to stretch it even a somewhat subdued form of genocide), themes that are out of reach for children to grasp. The film feels much more reminiscent of Golden Age Disney (Pinocchio, Bambi, Dumbo), or Tonari no Totoro, than it does to Kin no Tori, Wanpaku or Omae Umasou (I’ve never understood why Ettinger compared Catnapped to Puss in Boots or Doubutsu Takarajima in the first place, the film’s not “fun and games” at all, imo).

However, what I’ve found to be particularly interesting is how Ghibli seems to have taken a liking in Nakamura’s output. Someone correct me in case I am mistaken on either of these accounts, but 1) Neko no Ongaeshi is outright copying many of Catnapped’s most fundamental ideas and 2) only after Catnapped’s “on the nose” train-chase segment did Miyazaki start to abuse the living hell out of tunnels as visual motifs for children’s growth/adolescence (Sen to Chihiro, Ponyo, Howls – I don’t consider the thicket in Totoro to serve the same purpose, it’s used much more ambiguously; his latter films have their protags outright freeze in front of the tunnel). I’d be very interested in whether 1) or 2) had already been “a thing” before Catnapped (potentially some fringe-novel I am not aware of).

This one’s is a bit of a double edged sword. I think part of Banipal Witt’s incredibly diverse setting design can also be traced back to its art director: Shinji Kimura. While the initial ideas clearly sprouted from Nakamura’s head (sketches found as part of the Catnapped novel illustrate this fairly well), I am convinced for Kimura to have had a major hand in the meticulously crafted color-coordination which (at least to me) has always been one of Catnapped’s strongest characteristics. Therefore, Catnapped’s setting strikes me as the product of Nakamura’s balls on one hand, and the greatest(?) art director in animation history kick-starting his career as an artistic lead on the other. In addition, I’ve also found notable overlaps between the setting design for Peter Pan no Bokken and Catnapped, e.g. themepark’esque island floating mid air and – though this might be a bit of a stretch – the toy box aesthetic Richard Williams employed in pursuit of making his feature feature film, Raggedy Ann (albeit Catnapped sports much more competent color-coordination and much, much, much, much, much less ambitious (amounts/fluidity to its) animated motion).

Nakamura simply has an extremely warped understanding of viewer priorities. No wonder his works are comparatively “unpopular/fringe/overlooked”, especially among western fans. Like, how much of a post-war 50s boomer do you need to be to sell Palme no Ki as a children’s film, despite your first climax very graphically visualizing the decapitation of a man? Sure, Keiichi Hara kicked off Summerdays with Coo in similar fashion, but not only was his take much less aggressive/graphic, it also had strong thematic relevance. Meanwhile Koram chops off that random goons head because… uhm… so staff has an excuse to add religiously inspired symbolism?! Meanwhile Fantastic Children’s suffering porn similar to the likes of Fafner, Catnapped introduces the film’s most notable plot-point by letting the audience know how its protagonist physically abuses their pet, and Bobu to Bobulina’s about deception and panty-shots (while the protag’s dressed in full latex).

In conclusion: The guy simply sucks dick at making his creations appeal to a broad audience, and I say this as someone who considers him a top 10 creator in animation history (alongside the likes of Georges Schwizgebel and Garri Bardin). Shashinkan’s probably the most accessible thing he’s ever made, and it’s likely to also have been the (quasi) finale of a much less productive career than this medium deserved for it to be. But at the end of the day, I sincerely believe it’s him who’s to blame for this. Cause when you direct 6 things with little thematic or even aesthetic overlap, how the hell are you supposed to build a stable fan/customer base? Fuck his ambition… or something like that.

LikeLike

Thank you for your extremely detailed and complete comment! I don’t have much to say, you are making some very interesting and needed additions to my article. Getting too deep into Nakamura’s influences might have made me lose my initial focus in the piece, but I’m very grateful to you for citing so many of them.

I’ll just make a few remarks.

You cite the work of Thomas Lamarre and the animetism/cinematism distinction. To be fair, I’ve grown pretty distant with it and I don’t think it’s the best way to approach animation – for example, I think it might lead people to miss some artists’ proper individuality, as I think you do somewhat with Otomo. Of course, as you say, he didn’t invent pull-cels or the multiplane camera; but the way he uses it is so specific and intentional, I think it’d be a shame to just dismiss it under the (too broad in my mind) category of “animetism”.

As for Nakamura’s relationship to it – I’ll reckon his use of pull-cels is not as characteristic of Otomo’s. I still do, however, considering special, especially in the first works he directed until Catnapped. Considering that he did have such a close relationship to Otomo, especially on various shorts, I find it hard not to consider some sort of reciprocal influence – just as Nakamura’s designs both in animation and manga are very clearly inspired by Otomo’s.

I understand not being as interested by his work as animator, but I think that for figures like Nakamura (just like Miyazaki to give a similar example of great-animator-become-director), it can be very stimulating to look for the possible continuities between his career as animator and director. Although I don’t know in detail what was Nakamura’s exact level of influence over script and direction, his episodes of Gold Lightan are very interesting in that aspect – they clearly exhibit his own sensibility and influences. In a similar way, his use and progressive mastery of background animation can be reinserted into his general approach to animated space (in continuity or discontinuity with cinematism/animetism).

In any case, thanks again for your comment and insightful remarks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re right. Lamarre’s categories are too broad to classify films as, especially since many post 70s features can hardly be classified as either. I simply chose to refer to his book cause I assumed for you to have read it, and would therefore have an easier time perceiving what it is I am refering to. You might also be correct in accusing me of “denying Otomo unique traits as a director”, because – if I am being entirely honest – none of his works have ever struck me to share a notable amount of idiosyncratic elements (apart from the extensive panning, of course). Might be time for me to give his oeuvre another shot.

Poor wording on my end. I didn’t want to imply for Nakamura to not be indebted to Otomo, his style of directing or drawing. I intended to do – probably too contentiously so – was to point out how Nakamura (at least as far as I am aware) was influenced by non-Japanese sources to an extent few Japanese creators have been, which I believe to be one of the major reasons why – even by anime standards – he ended up being such a “unique” entity.

Agreed. Especially gven how Japanese KAs being in charge of their own layouts had been common practice at the time. I guess I simply have a bit of an axe to grind with western Sakugafandom, in how most of its members tend to obsess over “cuts”, while paying little attention to works at large. But you’re right: If one performs soloKA, odds are they had also been involved in the storyboarding/scripting process. You do bring up an interesting point, though. Because to me, venturing into the image has always been a way to make a world more believable, to make it feel alive, to free the animation from the flatness it often suffers from. Which means his focus/mastery of background animation would align pretty well with his pursuits to create the so called “illusion of life”. Which begs the question: Why distance yourself from this approach in such radical fashion (the Colorido shorts)?

LikeLiked by 1 person

To answer your last question very quickly – I’m no extensive expert of Nakamura’s work (I haven’t even seen all of it!), but from what I’ve seen it seems like he’s been exploring a certain direction during most of his career, but then moved on and explored another in these shorts you mention. They’re not in complete break with what came before, but his ability to change from one to the other without any visible loss in vision is certainly a proof of his talent.

(I also have to agree at least partly with your opinion on sakuga discourse. Though there’s surely a lot to be learnt by focusing on smaller units such as individual cuts or scenes – I hope what I’ve been doing on this series convinces you at least a bit of that)

LikeLike

To be fair, I don’t think anyone can claim to be. Apart from a handful of interviews and the snippets of information we’re being fed by his former associates (mostly Inoue and Okiura), there simply isn’t much (publically available) information on the guy.

Certainly. Though I’d still consider it much more interesting to watch you apply your knowledge to indepth episode/film analysis. Academic texts tend to focus on the same handful of movies ad nauseam. But that’s probably just me. Cheers.

LikeLike